Using Archetype

This is a guest post by Valentina Gettatelli

I recently had the chance to spend a few weeks hosted by King’s College London, at the Digital Humanities department and at King’s Digital Lab (KDL) working on a small proof-of-concept of the Archetype Framework as part of my Erasmus traineeship. Dr. Peter Stokes and Dr. Arianna Ciula have been my supervisors and led me to the discovery of this powerful tool and most importantly , gave me the opportunity to witness what happens when good academic research is supported by a team of information technology professionals. I would like to first share some thoughts on this and then consider some questions raised by using the Archetype framework.

The term “Digital Humanities” can cover a lot of areas , as far as human culture and informatics are concerned, so perhaps what we mean mostly by digital humanities is the digital applied to fields traditionally deemed having nothing to do with automated computational approaches. The digital humanities are now well established as a discipline but a lively debate is still going on, often focussed on finding a theoretical legitimacy to them. Although questioning its own methods and epistemic foundations is inherent to academic research, this debate may sometimes result in losing sight of the real objective of the research itself, at least from what I have seen in my brief experience of this domain.

At KDL the focus is not on the existential legitimacy of the discipline, but rather ensuring that computational tools are applied with rigour and respect for the complexity of the research domain.

I found the idea of devoting a whole interdepartmental team to the development and implementation of digital tools in order to explore cutting-edge research proposals to be a radical and exciting one. The field-tested workflow encompasses all the stages of the process, from taking into account embryonic ideas and turning them into promising projects, to helping researchers and scholars address the funding sources best suited to their needs.

Also, confronting ideas against the limits and capabilities of a digital architecture counts as a sort of a litmus test , which compels the proposer to sharpen their concept until it is clear and strong enough to be implemented. Strong and clear doesn’t mean fixed and immobile. On the contrary, as in the case of Archetype, a solid starting idea later proved to be flexible and scalable. Peter Stokes first conceived a framework intended to explore the vernacular English writing during the years 1000–1100. To do so he developed together with DDH and latterly KDL, a platform that can store visual resources and organise them with structured information. At the base of the framework there is a relational database in which a great many aspects of the process of handwriting is modelled. What I found more interesting is that this complex structure can be customised and lends itself to every kind of application in the humanities, as far as visual communication is concerned.

I was supposed to develop a small proof-of-concept of the framework within the paleographical domain using materials of my choice. When starting my small proof-of-concept, I didn't have any clear idea on how to choose some manuscripts rather than others. I thus decided to focus on some of the witnesses of the old French lyrics tradition. Choosing a sample corpus based on language and content it is not a paleographical criteria but it led to the collection of a fairly uniform set of documents from a palaeographical point of view.

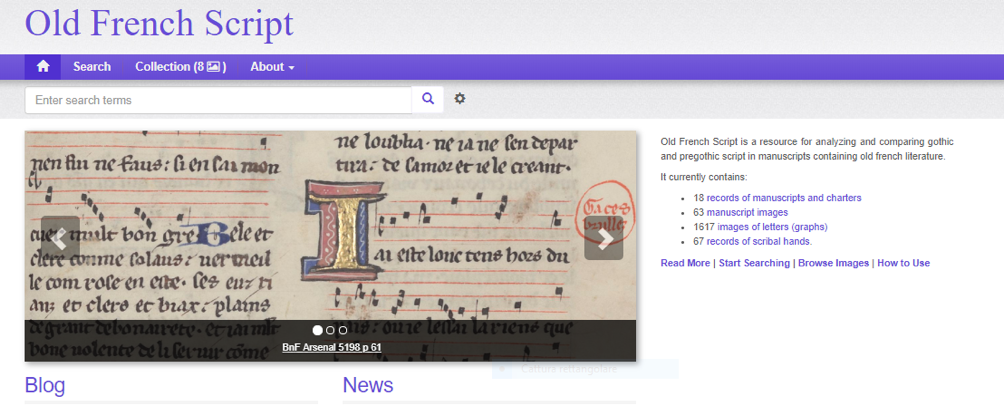

Homepage of my Proof of Concept

Using the Archetype framework is a two stage intellectual exercise: becoming acquainted with the architecture and then deciding how to develop your own work. The annotation process in Archetype requires a set of letters to be defined in order to describe the Graphs, that is, the actual appearance of the letters on the page. The framework is designed to focus on the morphology of the sign as it looks, without preconceived ideas.

Nevertheless the very nature of handwriting, excerpting exemplars from very formal and fixed kind of scripts such as Textualis Formata, is mostly variable and changing. It is therefore sometimes hard to keep faith with two basic principles which also seem to contradict each other: trying to describe the actual morphology of a graph and, at the same time, pinpoint its essential components; the ones that unambiguously identify it.

On one hand we are required to comply with a sharp and straightforward observation of symbols, on the other hand the need of fixing a certain number of components and features to describe a graph forces us to arbitrarily restrict the range of possibilities. In fact, we face the uneasy task to limit what we see to the extent in which it is included within the set of symbols we ourselves have previously defined.

It is difficult, for instance, to establish whether a given stroke is an intentional serif or it is accidental. Also, it is hard to decide which are the basic components of a letter and which are the optional features. Even when we think we have reduced the graph to its simplest expression, we might bump into a brand new form of that graph lacking one of those fundamental traits but still remaining recognisable.

This tension, necessitates a compromise between the description of the concrete sign as it stands, and a certain amount of abstraction. Also, for practical purposes, it may not be worth recording every slight variation in the appearance of a certain graph. The problem is striking when describing a set of very irregular scripts. Basically, doubts on procedural appropriateness might arise at any stage of the process: the temptation to endlessly extend the nomenclature for describing all the possible situations is strong.

I therefore experienced how using the framework fosters a fruitful observation of the script under enquiry and, most of all, leads the to question “which are the meaningful aspect to highlight?”, and to decide which characteristics, why they must be recorded and to what extent.

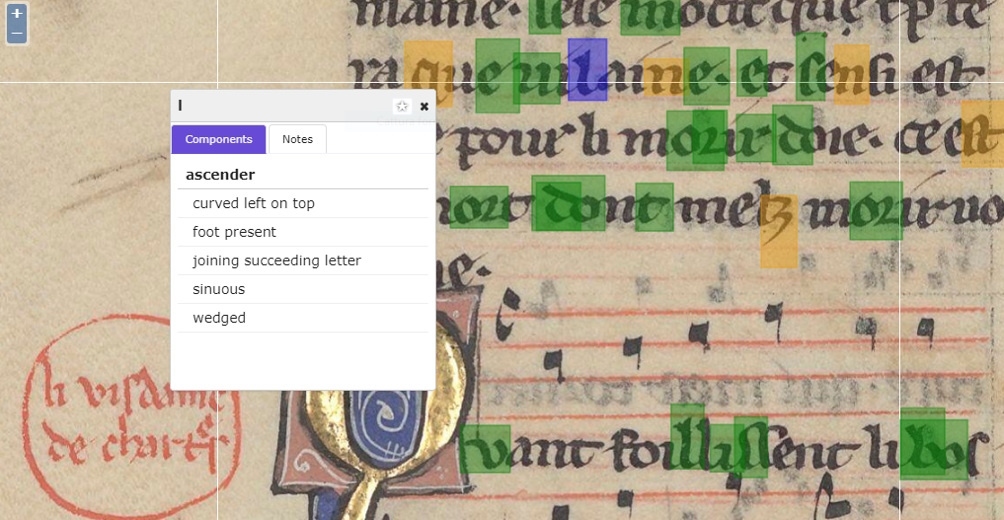

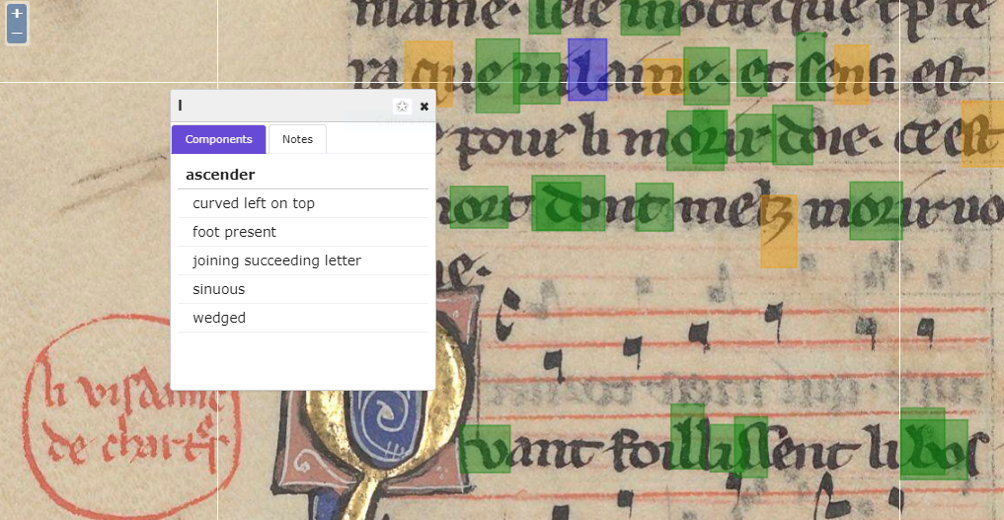

Example of an annotated page with graph description (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Arsenal 5198)

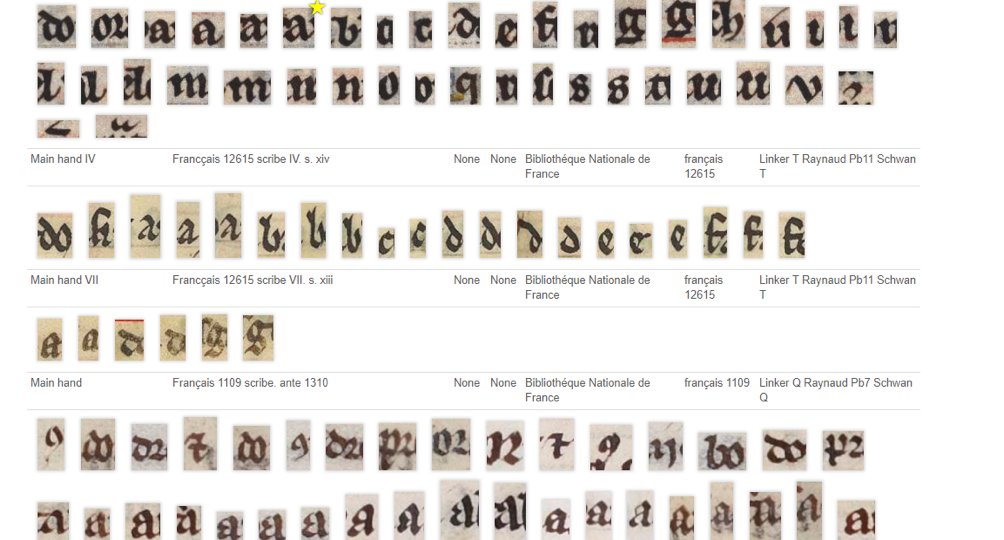

Annotated graphs - overview

So what to keep? What to leave out? How to name what has been kept? Using Archetype necessarily leads to establish criteria which allow selection of material to be described and build a vocabulary for that description.

Not being a palaeographer, it would have been very unwise to make up names that would end up making sense just for me. That is why I chose to rely on Albert Derolez’ authoritative work on the gothic and pre-gothic script, not only to learn more on the subject, but also to set a shareable lexicon for describing the Allographs and their components and features. But, what is more important, the overview on the script along with what the scholar chose to talk about at length, helped me to decide what is worth describing and what is irrelevant for an overall understanding of the writing system I am dealing with.

And that’s the point: using the framework does not exempt the user from a profound competence on the matter. On the contrary, this tool provides a testing ground for that competence and, what is more important, the scholar deciding to publish their own material and annotations on an Archetype instance is compelled to make transparent – to himself and to others - the research rationale, the procedural solutions she adopted and the analysis outcome.

Using a powerful digital tool leaves full discretion to the researcher, but makes the process accessible and open, thanks to the evidence of the annotated image. Furthermore, the idea of a framework capable of storing a large volume of visual resources with structured annotation is both simple and powerful, and it will be interesting to see how it will be adopted and adapted to the most diverse areas of application in the humanities, and to the creativeness of different scholars.