Reflections on the International Indigenous Librarians’ Forum

A colleague asked, “What was it like attending a conference based in Hawaii compared to the usual other locations?” which is a useful question to answer. The International Indigenous Librarians' Forum (IILF), which has been going since 1999 is hosted by a different country usually every two years, but this was the first time Hawaiʻi has hosted and it was the largest yet. I’ve attended four IILFs so far, two in Aotearoa New Zealand, and two in the US – one on the Lummi reservation in Washington State, and this one in Hawaiʻi. Hosting IILF in Hawaiʻi meant many more Kānaka Maoli could attend than any of the forums I’d previously been to and it meant that the conference was grounded in their language, practices and protocols.

This isn’t to mean that the beauty of the islands wasn’t an attraction to attendees – it certainly was – but what it meant for a number of us was an invitation to step foot on the lands of our whanaunga, our Pacific Island relations, in a respectful manner that didn’t reflect the ongoing colonial violence and touristic exploitation that plays out in the islands of the Hawaiʻian Kingdom.

It’s been several years since I’ve been an acting librarian, having changed roles when I began working at KDL, but there is still a strong alignment between what I do and those in the information management professions, so I always learn a lot attending IILF. I am also nourished in ways that are difficult to articulate in English when I am among other Māori and Indigenous people who are engaging intensely in what it means to be Indigenous.

Following tradition, conference opened the first day with ceremony – this time our ceremony encompassed the spiritual practices of our hosts and incorporated the exchange of the Mauri Stone and offerings of gifts that were laid on the shelves of the Lele, built specially for the welcome. We offered songs (me humming during the bits where I didn’t know the words!) and koha, others offered speeches, songs and the Métis danced. We were out at Waimea Valley, a sacred space for Kānaka Maoli, and after the ceremony we had the opportunity to explore the Valley and talk to those who guide and work there. It is a beautiful place, alive with native birds, frogs, lizards and with lush trees, mosses and other plants. I sat and listened to a woman speak as she pounded kapa cloth in the grounds of the archaeological village.

Tuesday, and each subsequent conference day, opened with a prayer. These are often led by elders and frequently spoken in a different indigenous language each morning. Hauʻolihiwahiwa Moniz and Kapena Shim, the forum co-chairs, followed up to introduce the keynote panel of four Kānaka Maoli librarians (Kylie Flood, Ikaika Keliiliki, Kawena Komeiji, Keahiahi Long), ‘E Mau Ke Ea Revealed: The Journeys of Kanaka Librarians Towards Indigenous Sovereignty’, moderated by Lessa Kananiʻopua Pelayo-Lozada, immediate Past President of the American Library Association. It was a great first keynote with frank discussions around librarianship as a second-choice career for many, strongly motivated through connections to sources, seeing yourself in there and connecting others to the knowledge held in those sources. The conversation then ranged out to exercising agency, culture as resiliency, and whakapapa research as strength. The panelists talked about how learning our histories cannot be a privilege – it is a necessity for us to be able to be in a place of thriving. Other points covered included: exercising sovereignty as an expression of identity; finding your people; holding your boundaries; and the importance of learning to say no (and also yes). Speakers advised allies to listen, make space, and to learn on their own rather than placing that labour on Indigenous colleagues.

The first of the parallel sessions I attended was ‘Indigenous Presence: Grounding Place in Academic Libraries.’ This paper was given by Ashley Edwards (Métis, Scottish, and Dutch) and Rachel Chong (Métis and mixed European), both presenting their experiences of developing Indigenous spaces at two academic libraries – both on lands belonging to other first nation groups. Both speakers highlight the importance of inclusion of material that speaks to different literacies including: visual, in terms of design, pattern, art, colour; oral literacy; and relationship-based literacy, an example given was tea and bannock sessions. The speakers noted that they were careful to identify their positionality as being not from the lands where they work. I was tangentially involved in something similar whilst working at Victoria University of Wellington Libraries and it was really interesting to hear of other approaches. As my work now is almost entirely in the digital sphere I am always interested to learn of what occurs in physical spaces and as a weaver I love to see how visual literacies are incorporated.

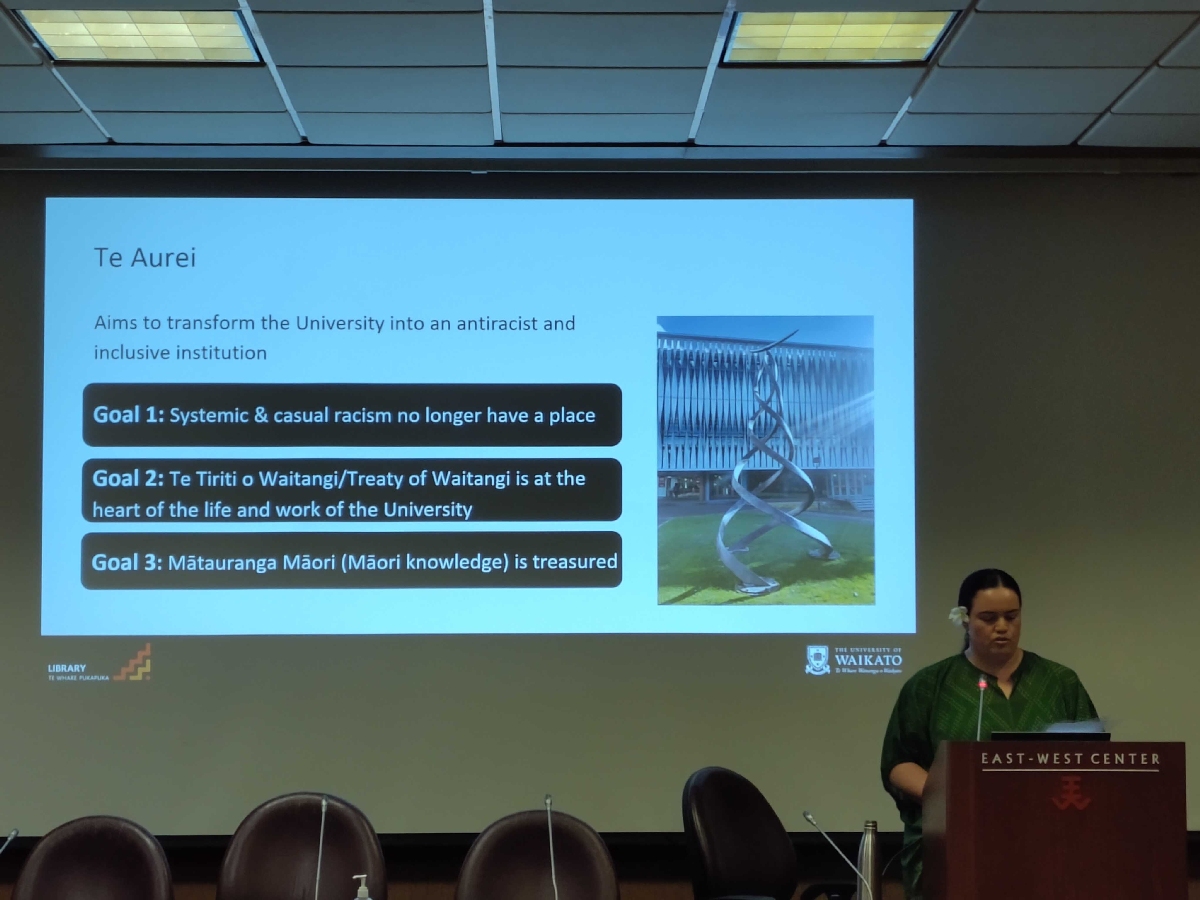

The second Tuesday session I attended was ‘Ko te tangata (For the people): Indigenising the Library at the University of Waikato’ presented by Rangihurihia McDonald (Ngāti Maniapoto). As Pou Ārahi (Cultural Lead) at the Library of the University of Waikato, Rangihurihia spoke of the implementation of indigenisation and anti-racism steps being taken at her library. I found this session pertinent, especially in terms of commonalities and differences with the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion work that happens at my own institution. There was a lot of good learning to take from this session (I hope to share her conference proceedings with staff here at King’s) but one of the steps that sparked a lot of follow up questions was that staff are required to have at least one anti-racism goal on their development work plans. They do not prescribe what these might be, or the scope, so anti-racism goals could be as simple as reading some of the supplied resources.

In the afternoon, when the sun made a surprising appearance after almost continuous rain, we made our way to the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, who would host us in the afternoon for the Lā Kūʻokoʻa celebrations. 28 November is when Kānaka Maoli celebrate the day, 180 years ago, that their, “...sovereignty was secured internationally by the signing of the Anglo-Franco Proclamation in 1843.” This saw England and France recognise the sovereignty of the Hawaiʻian Kingdom. Following this declaration Hawaiʻi was to secure further acknowledgements of independence from other countries, including the United States of America.

The celebrations were opened by a keynote from the Director of Ka Papa Loʻi o Kānewai, Kumu Makahiapo Cashman, speaking to '’Aina as a Library' especially in relation to the Loʻi or kalo (taro) gardens that they have on centre grounds. This was followed by opportunities to listen to guided tours of the Loʻi, the Center library which is a beautiful space with gorgeous artwork, and an area to talk to publishers, educational organisations, artists and artisans.

Afterwards we enjoyed a dinner of traditional Hawaiʻian food including poi, laulau, kalua pig, lomi-lomi salmon and more. I enjoyed trying all the foods but could faintly hear the grumbles from the taro loving folk among the guests who were confused by the texture of poi as it is entirely different from how we usually eat it in the South Pacific. During dinner we were entertained by the music from the Tuahine Troupe and hula performed by the next keynote speaker, Dr. Kuʻuleilani Reyes, and others which was wonderful and had an authenticity that I suspect is missing from the for-tourists luaus down in Waikīkī (we thought we heard a terrible attempt at haka at one while we were walking past and had to hotfoot away before we went and had Loud Opinions and possibly got arrested). Dr. Reyes spoke with passion and to the tensions that arise in a school where children are taught Hawaiʻian language and ways of being and a small group of parents express concerns that what their children are learning isn’t Christian.

The day I was to present, Wednesday, started especially soggy in the sort of drenching rain that soaks almost instantly. I took a change of clothes with me as I walked to campus and I am grateful for the forward thinking of my past self. Our keynote that morning was Pua Case, an activist and educator who advocates for her sacred mountain, Mauna Kea, which has been the subject of conflict between Kānaka Maoli and others, and those intending to build a large telescope upon the mountain. This keynote resonated with me and my volunteer work with Te Maru o Hinemihi – the sacrifices we make, the work we do, to honour Hinemihi o te Ao Tawhito, those in the past, our ways of being, and our future through our community children and meeting their needs.

The first of the Wednesday parallel sessions I attended included two presentations - Danica Pawlick-Potts (Alexis Nakota Sioux) spoke to ‘Re-using Data in a Good Way: Working Towards Data Repositories Designed to Respect Indigenous Data Sovereignty’ while Chris Cormack (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha) and Aleisha Amohia (Te Atihaunui a Paparangi, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Hāua, Cambodia, India) spoke about ‘Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Libraries’ more generally and its relation to Māori Data Sovereignty more specifically. Since respecting Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDSov) is something I advocate for in my work and outreach I found both these talks really useful to understand the way existing systems can and cannot support IDSov, how IDSov approaches can be built into Research Data Management policies, ‘full stack’ control of data, mindfulness of context and what to consider in terms of harm minimisation from GAI and LLM models developed by those external to ourselves.

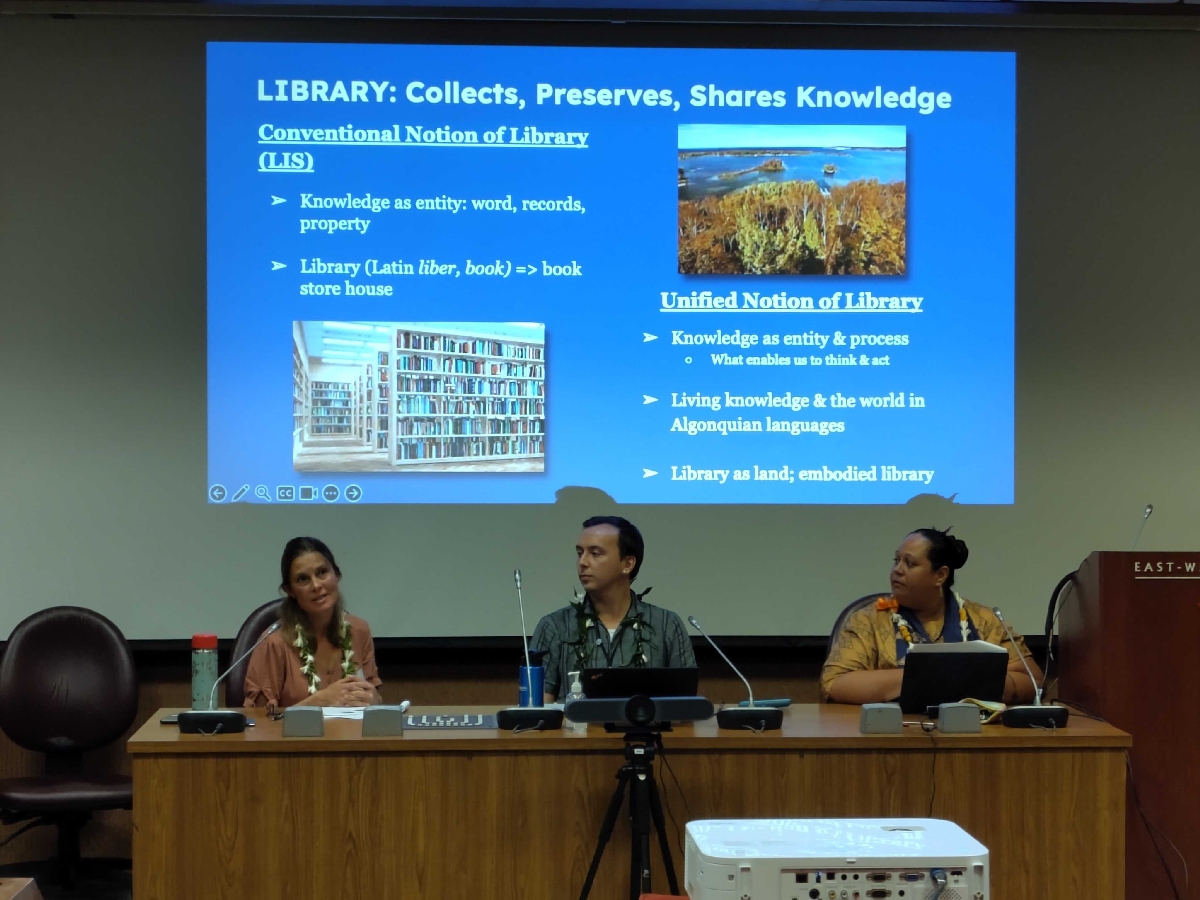

The late morning session I attended was for ‘Spaces of Being: Indigenous Embodiments of the Library’ presented by Keau George (Kānaka Maoli), Brandon Castle (Tsimshian [Alaska Native]) and Ulia Gosart (Udmurts [South-eastern Siberia]). They ask, “how do Indigenous libraries serve their communities to preserve knowledge in non-textual form?” They discussed what could constitute a ‘library’, knowledge libraries as processes, embodied libraries on the land, in place, tangible and intangible libraries and the communities of practice around them. There was discussion around preservation of libraries as preservation of communities versus maintaining records without care for communities. A lot of great examples were given; totem poles, hula, walking paths on the Channel Islands off the coast of Los Angeles, as well as language as a living library.

Finally, it was my opportunity to speak, which I think went well – it was great to present KDL's Indigenous Digital Humanities research theme to interested people.

The late afternoon and early evening were taken up with a kanikapila, “a casual, traditional Hawaiian gathering in which food, music, song, dance, and conversation are shared in honor of fellowship and relationship-building. Delegates...[were]...invited to bring their voices and instruments!” This was a lot of fun, with many different groups and people sharing songs or dances from their communities, or just taking the opportunity to karaoke to the crowd. I sang along to the songs I knew and laughed a lot.

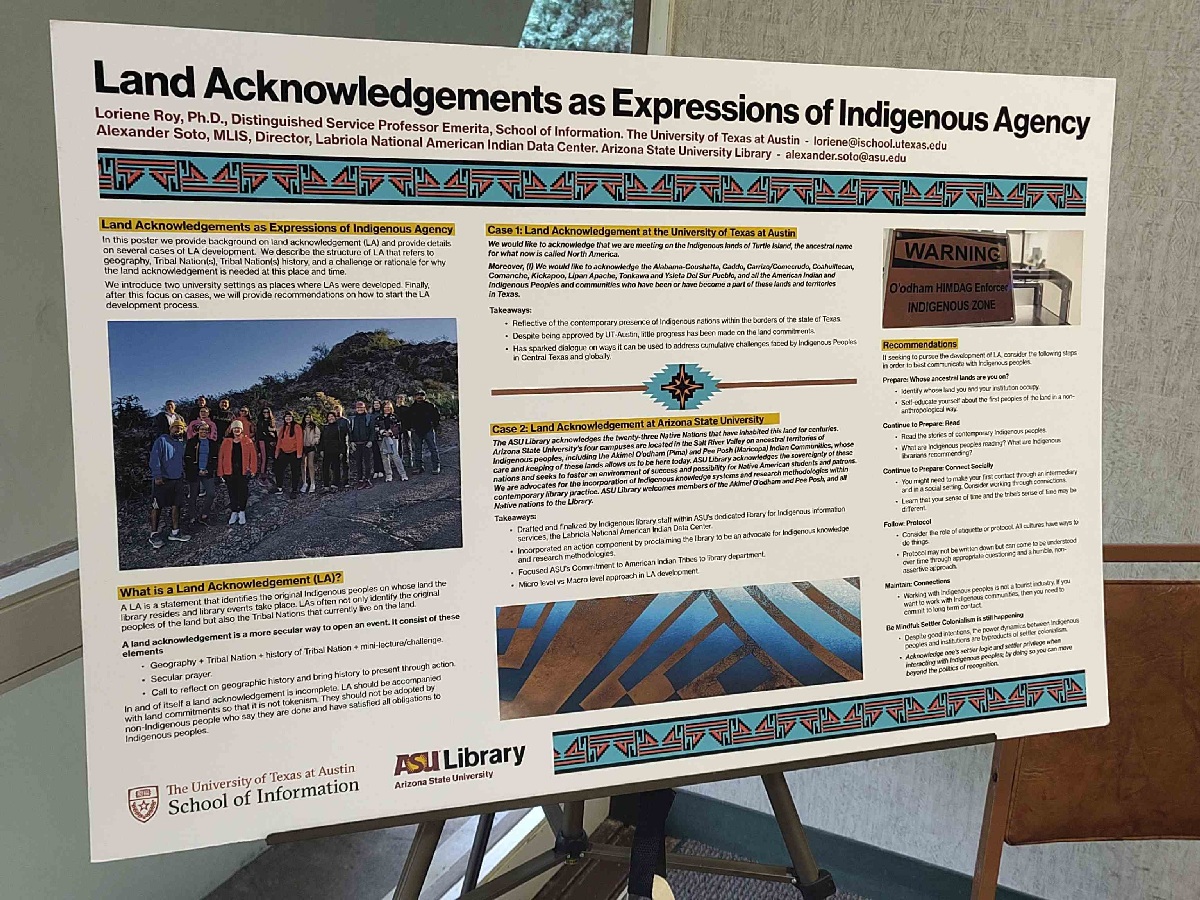

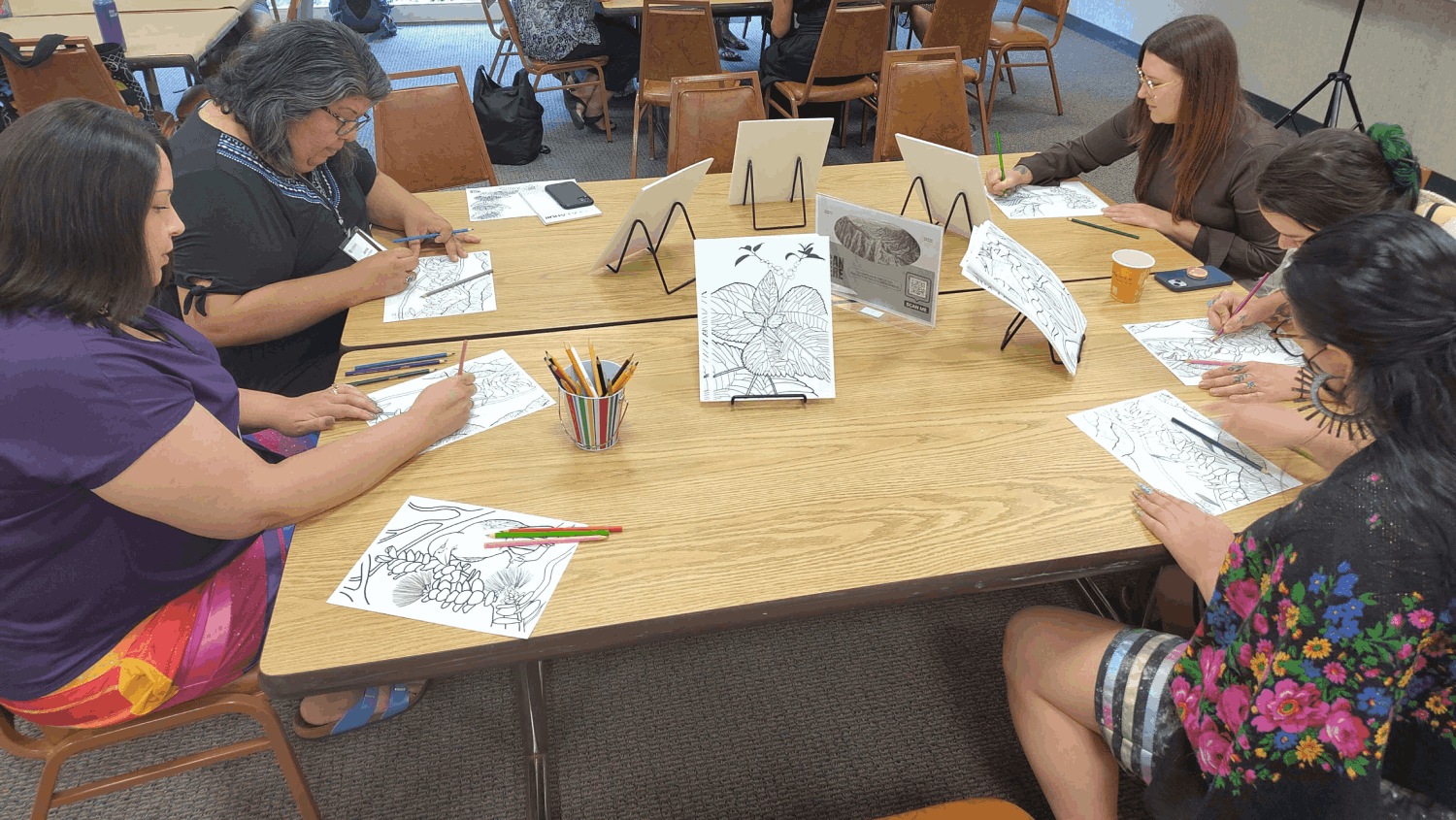

Thursday was the final day of conference and began with the poster exhibition and an opportunity to discuss them with their creators. I got to meet and talk to some, including Julie Fiveash, Librarian for American Indigenous Studies Tozzer Library, where we, and another, discussed the Indigenous boardgame group she hosts and how much we all enjoy the game, Spirit Island. In IILF tradition, we then split into two groups – one indigenous, the other allies, to speak together to our particular interests and needs. At past IILFs, the Indigenous attendees have often sat around a room or in a lecture hall and discussed topics of interests that have arisen from the forum. This forum the approach was a little different – you could colour in or weave or learn how to play a Hawaiʻian board game and chat with your fellow attendees; I had a long discussion with Stacy Allison-Cassin, a Métis colleague that I met first at a Linked Open Data in Libraries Archives Museums (LODLAM) summit in Venice in 2017. There were dedicated discussion groups around topics like Indigenous futures and then an open mic session at the end where, in a first for any conference I have attended, a librarian rapped. The breakup into groups, Indigenous and ally, allows us to speak freely and without concerns of offending which can be a very rare occurrence for some of those working in the library and information management sectors, especially as often you may be the only Indigenous person in those spaces.

Finally, we came back together for the closing of the forum. The final keynote speaker was Kahele Dukelow who defined the term ‘Aloha ʻaina’ for us, aspects found within that concept and the practices that support it. She spoke of the history of Hawaiʻi and of history education there and how we can actively think about the ways we share our privilege, our knowledge, with our communities. Hauʻolihiwahiwa Moniz and Kapena Shim spoke to what had been covered by the forum as a whole and then we had another open mic session where attendees offered their thanks to our hosts and the forum in the forms of poems, songs, speeches, chants and prayers. Others took the opportunity to remind attendees of their privilege to be able to attend when others could not due to a failure of support. A final song all together and we were done.

Another colleague asked: “My main question would be: did the format meet expectations of a conference with indigenous mind sets? or after all very much of the same? and if the format was the same, was the content different? Inspiring?” Part of IILF is very much the same as many other conferences – there are papers presented, posters displayed, panel discussions and keynotes. However, their focus and grounding are almost always on Indigenous ways of being and engaging with the world. The keynotes are often from outside the information management sector and activists within their own spaces. IILF is generally opened with ceremony, according to the host’s practices and there are many opportunities given to experience the whenua/land on which we are hosted, to meet with community members, to eat traditional foods and watch cultural performances, to try out some cultural practices and to be together, unapologetically, as Indigenous people. I always find IILF inspiring, deeply interesting, and a wonderful opportunity to learn from colleagues working in and alongside the sector.

I returned on the long flights from Oʻahu with a check-in bag miraculously under the weight limit despite the number of books I had acquired (some bought, some gifted from our hosts – a library conference without book acquisition would be strange indeed) as well as the Ti leaf lei that I was gifted at the opening ceremony. I am very happy to have attended and grateful that KDL was able to support my attendance.