Exposing legacy project datasets in Digital Humanities

How to address pragmatically the substantial challenge of curating and archiving a rich estate of over 100 legacy projects without funding? Deep breath…

In this blogpost we share our experiences at King’s Digital Lab (KDL). While we can call the process a success overall (and you can read more about it in this article and in the summary of our current archiving and sustainability approach), the road has been bumpy and we stumbled across some interesting challenges along the way. In this blogpost we talk about how we made use of the Open Knowledge Foundation’s open source data portal platform CKAN to catalogue and make visible some of our legacy projects’ data.

KDL adopted CKAN following assessment of the institutional repository in place at the time as well as comparisons of research data management platforms in the literature (e.g. on ‘data FAIRification’ see van Erp, J. A. et al. 2018). While this is a solution that might encounter changes over time (including data migration or mapping to and aggregation in other repositories), at the moment it is fit for purpose in that it provides a metadata catalogue to store or to point to some of our legacy projects datasets - and associated contextual documentation - which were not accessible before, expanding substantially the potential for data and resources to be discovered, re-used and critiqued.

First things first, a step back to what KDL is about and what the data we inherited and produced entail. KDL builds on a recent yet relatively long history - for the field of Digital Humanities - of creating tools and web resources in collaboration with researchers in the arts and humanities as well as the cultural heritage sector. While KDL started operation as a team of Research Software Engineers within the Faculty of the Arts and Humanities at King’s College London (UK) in 2015, some of the projects we inherited were developed 5, 10 or even 20 years before the Lab’s existence. Out of the ca. 100 legacy projects, some started in the late 1990s or early 2000s out of many collaborative projects led or co-led by the Department of Digital Humanities (DDH). The tools and resources KDL inherited span a wide spectrum from text analysis and annotation tools, digital corpora of texts, images and musical scores to digital editions, historical databases and layered maps.

The resources you will find in the KDL CKAN instance aren’t numerous but our plan is to increase their number as further support is obtained for a project undertaken by KDL (in particular with the involvement of Samantha Callaghan, Paul Caton, Arianna Ciula, Neil Jakeman, Brian Maher, Pam Mellen, Miguel Vieira, Tim Watts) in collaboration with colleagues and students at the Department of Digital Humanities (Paul Spence, Kristen Shuster, Minmin Yu). This work was a continuation of the wider archiving and sustainability effort described in Smithies et al. 2019 article and was possible through a seed fund grant offered by DDH and complemented by a student internship on the MA in Digital Humanities.

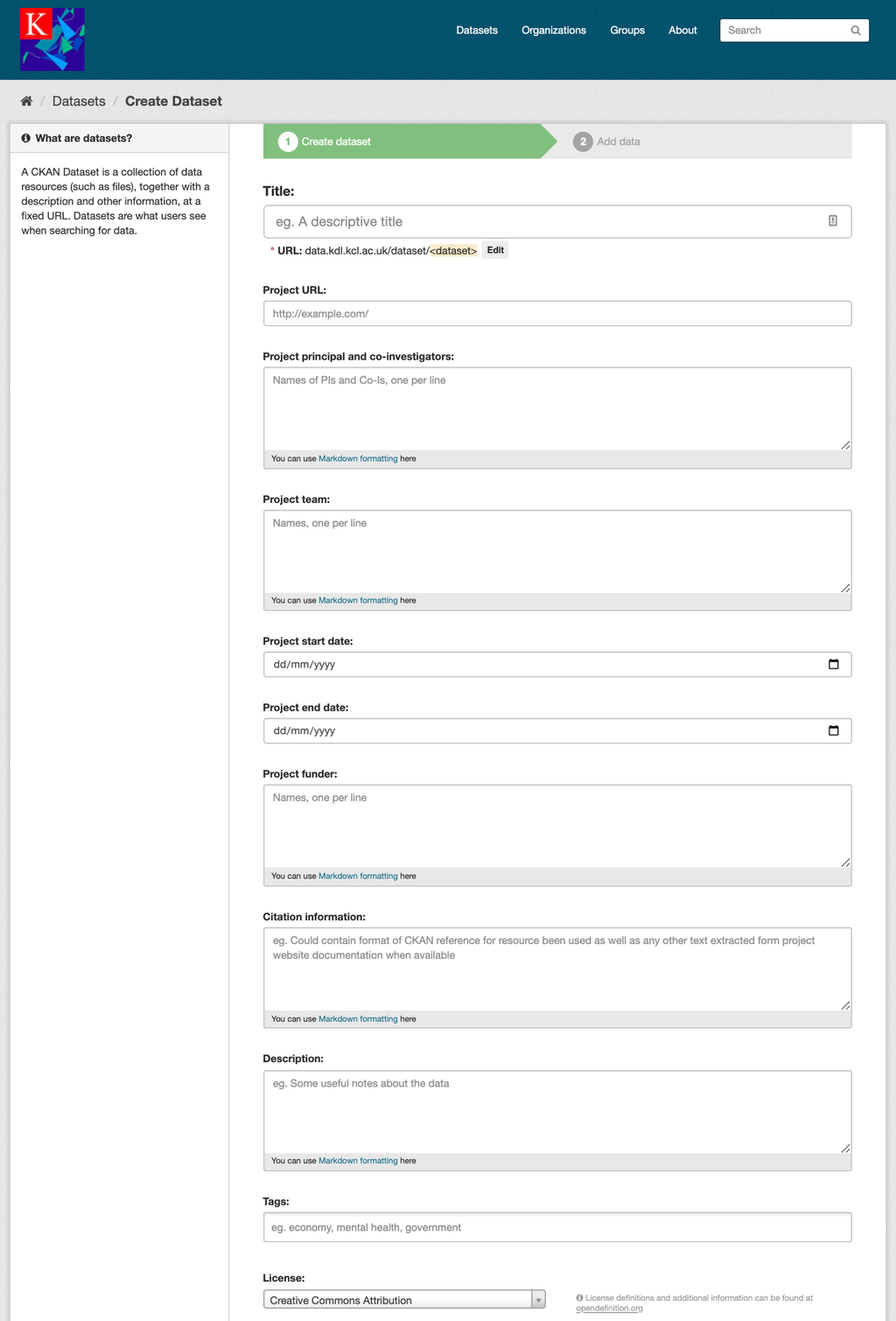

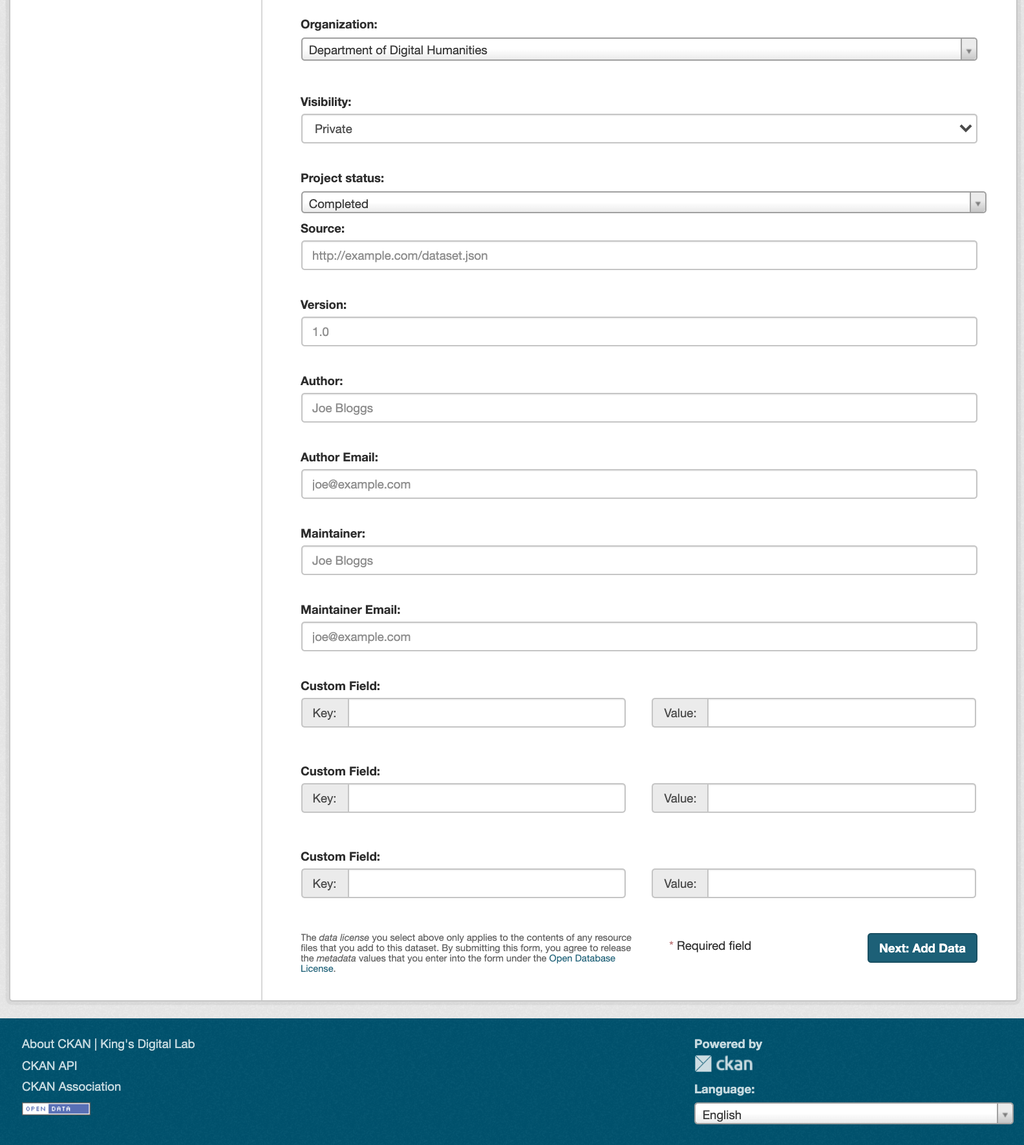

The datasets and resources we collected and catalogued range from summarised (so called ‘calendared’) editions of medieval documents to collections of modern correspondence, from ontologies adapted to express complex entities and relations in medieval documents to corresponding guides for encoding and data modelling. The default CKAN mask mapped to international cataloguing standards allows the capture of important dataset information such as creator and maintainer details, version etc. However, given that our legacy datasets are mainly project-based, we also decided to enhance the catalogue with project metadata (see related code at our github repository) ranging from information about the collaborative teams (typically including academics, archivists, designers, software engineers, analysts) to details on funders and period of activity. This slight modification of the data ingest form was then re-used in a currently active project - MaDiH (مديح): Mapping Digital Cultural Heritage in Jordan - which is looking at scoping the landscape of Jordanian cultural heritage datasets and also opted for a KDL-hosted CKAN instance as its core solution architecture (the code associated to other MaDiH-specific CKAN extensions including detailed tagging for time periods and data types is available at this other github repository).

The CKAN mask for KDL instance (part 1)

The CKAN mask for KDL instance (part 2)

What follows is the workflow we implemented for our cataloguing project:

- Dataset and resource selection

- Preliminary data entries by analyst and/or supervised student

- Internal peer review

- Communications with partners providing project overview, outline of benefits, some technical details (information on CKAN, list of resources to be exposed, license for the data, preview details) and requesting consent

- Data publication (if consent obtained)

- Public comms and dissemination (e.g. on social media)

- Creation of Digital Object Identifier at dataset level via DataCite membership of King’s College London library

- Update of citation field when DOI obtained

With respect to point 1 and 2, the cataloguing information provided for each project (equivalent to dataset in CKAN parlance) is rather high level; however, even at this rather minimally functional level, more often than not, digging into legacy documentation is not trivial and requires making tacit knowledge within the lab explicit or contacting partners to elicit further context, information and rationale for resource selection and ingestion.

For example, despite KDL legacy projects being informed by best practices in digital humanities such as use of standards and general openness to data re-use, licences were not always agreed at the time of data creation, in some cases leaving room for interpretation or substantial discussions regarding data ownership and exposure. In addition, in academic research, even when projects are long completed and unfunded, often collected and created data continue to be manipulated and analysed to inform further research and new arguments. While we had agreed to expose data which were considered ‘complete’, often multiple versions of the ‘same’ resource co-exist (adequately time-stamped or contextualised in narrative form) to showcase the constructed nature of this material and their workflows.

Data exposure and publication has now become a key element in King’s Digital Lab’s approach to project development as well as to our archiving and sustainability model. Dataset deposit within the Lab or as part of institutional technical systems as well as external repositories is an option assessed at several stages of a project lifecyle, from initial conversations with project partners when discussing a new project idea to post-funding phase and maintenance of legacy projects (see more on our approach on this guidance to research data management). Data publication on the KDL CKAN instance addresses mainly the issue of hidden datasets for our legacy projects at the moment; however, cataloguing projects metadata and exposing project datasets via CKAN is one of the options KDL currently offers also to new project partners.

Not only can shifting from systems to data ease the maintenance burden of many long-running projects, but it opens up possibilities for data re-use, verification and integration beyond siloed resources. Data exposure is however not enough to ensure access, and should not mask the need for attention to standards, workflows, systems and services (see recent ALLEA report on “Sustainable and FAIR Data Sharing in the Humanities”). This is where attention to tailored project solutions to research questions and domains while at the same time attempting to align to existing community standards within the Linked Open data paradigm continues to be a challenging yet fruitful area of research and ongoing activities at KDL. For example, our research software engineers are currently working towards integrating the web framework application most used in KDL’s technical stack – Django – with relevant APIs to align to specific standards (e.g. bibliographic RDF data models; Linked Open Data resources for people and location entities) or to extend them as needed with project code published on relevant software repositories (see https://github.com/kingsdigitallab/) under an open licence.

Sleeves up as there is a lot of work still to be done...