How KDL applies Machine Learning to research projects

As our new director, Arianna, mentioned in her recent blog post, Machine Learning (ML) is one of the research themes we are keen to start prioritising. Not only because it matches strong personal interests among the solution development team who are eager to experiment with new and exciting techniques (as you would expect from a Lab) but also because, as AI research moves quickly, it continuously brings new methodological opportunities to many scientific fields including the Humanities.

This blog post comes at a time when there seems to be a noticeable step change in the attention given to such new opportunities during our pre-grant feasibility studies (when requirements for a project are discussed to assess technical feasibility before design and development begin). This obviously reflects transformations caused by AI within research fields and brought to our attention by our project partners. It also coincides with the relatively recent explosion of open-source machine learning tools ignited by a handful of extremely versatile deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow or Pytorch. Thanks in part to the end-to-end property of Deep Learning (DL), many of those tools are deceptively easy to use (even with limited programming or AI skills) despite the new level of complexity of the tasks they can tackle. More on the flip side of that coin at the end of this post.

Use Cases

Illustrated below are different facets of AI applied to a variety of projects I contributed to over the years (from legacy to new projects), with some notes on the reason why I used them and hopefully some interesting insights into our Research Software Engineering (RSE) processes. My colleagues will soon share their own experience separately as part of this new series of posts on ML to complement this very subjective and partial retrospective.

Early English Laws (2009-2011, AHRC, PI: Jane Winters)

Context: Our research partners requested a web visualisation of the dependency graph among early English legal texts (10th to 13th century) where a node represents a text and an edge indicates textual borrowing. Each law code has its own graph centred around it (Cnut’s Winchester code or I–II Cn, in the screenshots above). When a graph gets more crowded, arranging the nodes into an elegant and readable layout is tricky. At the time I didn’t manage to design (or find) a good layout algorithm for our specific needs.

Use case: I decided to define what makes a good layout (e.g., vertically compact, without overlapping nodes or edges crossing each other), design an objective function that attributes a score to a layout according to those conditions and use Differential Evolution to iteratively improve an initial population of random layouts until they efficiently converge to a minimum of our objective function. Machine Learning tends to shift the development work from algorithmic (how/imperative) to requirements (what/declarative) modeling which is more abstract and intuitive. Moreover, although the end results are not always optimal, this approach copes gracefully with configurations where an ideal layout is impossible (e.g., crossing edges are sometimes unavoidable, but will be minimised).

Exon Domesday (2014-2017, AHRC, PI: Julia Crick)

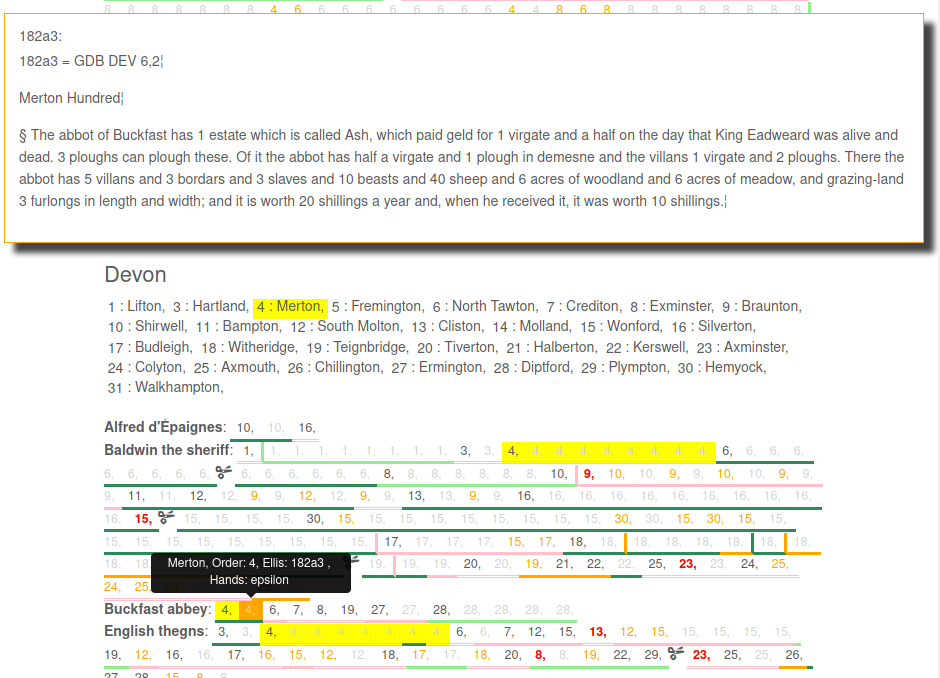

Hundredal Order page on the Exon Domesday project website (introduction by P. Stokes).

Context: The entries in the surviving copy of the Exon Domesday book are grouped first by owners of the lands then by their locations or hundreds. I developed a web application to allow the researchers to visualise the sequence of hundreds among owners and identify possible patterns that could shed some light on the method of production of the Domesday survey and the assembly of the book. The experts came up with their own pattern for each County. The interface automatically highlights all entries that deviate from that pattern in the Exon Domesday book.

Use case: I adapted the metaheuristic developed in Early English Laws to find a sequence of hundreds that would minimise the number of deviations (i.e. our objective function) to see if it could come up with new sequences the researchers hadn’t considered. I did this by implementing a Genetic Algorithm with crossover & mutation operators specially adapted for combinatorial optimisation. In this case Machine Learning complements rather than automates the research by offering new, albeit ahistorical, analytical suggestions. This form of suggestion works particularly well within such an exploratory web interface where patterns are easy to interactively inspect. It is also interesting to note that each time the algorithm generates a sequence, it is slightly different. That’s because the method is stochastic and there is no single perfect solution to this problem.

The Community of the realm in Scotland (2017-2021, AHRC, PI: Alice Taylor)

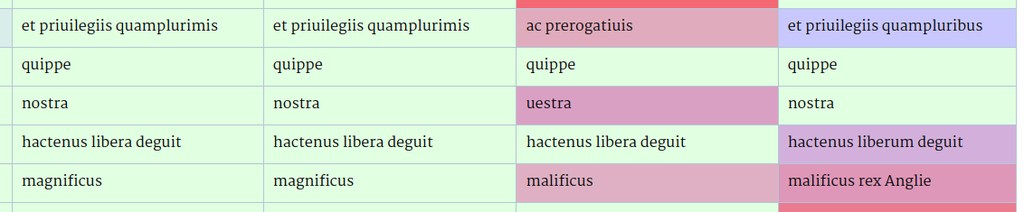

Collation table with colour-coded textual distances. (See also the Help page).

Context: Near the end of the project development, I quickly experimented with an online collation table of the copies of the Declaration of Arbroath. True to the idea of a Dynamic Edition, it displays user-selected copies side by side, without hierarchy, free from of the bias of what is known as a version or as the original copy. In each row the ‘readings’ are colour coded to intuitively convey the grouping among similar readings and the sense of textual distance. After formally exploring the multifaceted notion of distance (spelling, added words, word lengths and order, degree of disagreements among sources, ...) among a set of readings, and quantifying it with various metrics (e.g. Levenstein distance), my colleagues pointed out that the difference in meaning was not accounted for (sometimes a few letters can completely transform the meaning: e.g. magnificus → malificus).

Use Case: I tried to estimate the semantic distance by converting the words into static embeddings using a public domain, pre-trained Latin language model (since our corpus is too small to train a new one), averaging the vectors for each reading and comparing the readings with a cosine distance. The result isn’t very convincing, even for single word readings, perhaps because the model I found had been trained on very different types of texts (including Latin Wikipedia!) but also because embeddings tend to capture (sometimes a loose notion of) relatedness rather than similarity.

Classification of legal texts (2020-2021, pre-grant analysis, KCL History department)

This project is quite different from the previous examples. The primary research objectives are heavily reliant on the ability to (semi-)automate the classification of a large quantity of legal texts according to a predefined taxonomy. This time an extensive evaluation of different types of classification models was seed-funded during our pre-grant analysis phase because the feasibility of the entire project depends on it. In this case Machine Learning (ML) is a core requirement, rather than an optional method suggested by KDL during the funded Agile development phase to enhance the research or its output.

Use case: text classification is a very well-studied type of ML tasks with many available methods to choose from, often already packaged into ready-made tools. However, the relatively small amount of training samples (which is quite typical for niche historical corpora) and their very uneven distribution into a high number of very specific subcategories proved quite challenging. Moreover, the phrasing and vocabulary are particular to the period, geography and the legal domain under study. I fine-tuned more advanced and freely available language models (such as Transformers) already pre-trained by other research teams on much larger datasets of contemporary legal texts to reach accuracy level which I estimated could be sufficient to make the rest of the project activities possible. Searching for the right model architecture and the best set of training hyperparameters - very sensitive to different pre-processing of various parts of the texts - can be extremely time consuming and requires powerful computers with high-end graphic cards.

Word alignment across translations (2022, pre-grant analysis, PI: Gabriele Salciute Civiliene)

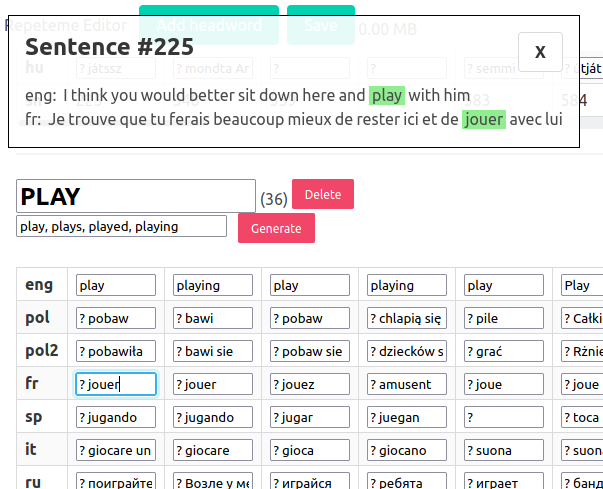

Proof of concept of a semi-automated word alignment interface, inspired by the concepts developed by Gabriele Salciute Civiliene

In this pre-project (the pre-grant analysis that feeds into an application) phase, semi-automation of the alignment of instances of selected word forms among different translations of the same text was identified as an important pre-requisite to reduce highly repetitive manual labour and substantially extend the size of the research corpus. I have compared the performance of four open-source implementations of two approaches (IBM Alignment models and Attention extraction from pre-trained multilingual Transformer models) on a dataset manually labelled during an earlier pilot of the project also led by the same PI. Interestingly the state-of-the-art techniques proved less accurate, less consistent across languages and harder to configure and execute than its 30-years old counterpart (IBM models). I also built a proof of concept of an interactive editorial interface on top of the automated word aligner to let researchers quickly review and correct its suggestions. The interface is heavily inspired by earlier concepts designed by Gabriele Salciute Civiliene. It is worth noting that I managed to carry out this experimental work during the feasibility stage (i.e. pre-grant application) thanks to KDL “10% time” scheme (a ‘protected’ portion of each KDL RSE team member’s workload model carved out to experiment freely and independently from projects requirements and schedules).

This is only a sample of use cases. In other projects in the Lab we are also applying topic modelling, text summarization, hierarchical clustering and neural search to help other partners discover major trends among their projects datasets. For example, my colleague Miguel Vieira has also recently fine-tuned generative language models to produce fictional narratives about the provenance of real heritage material.

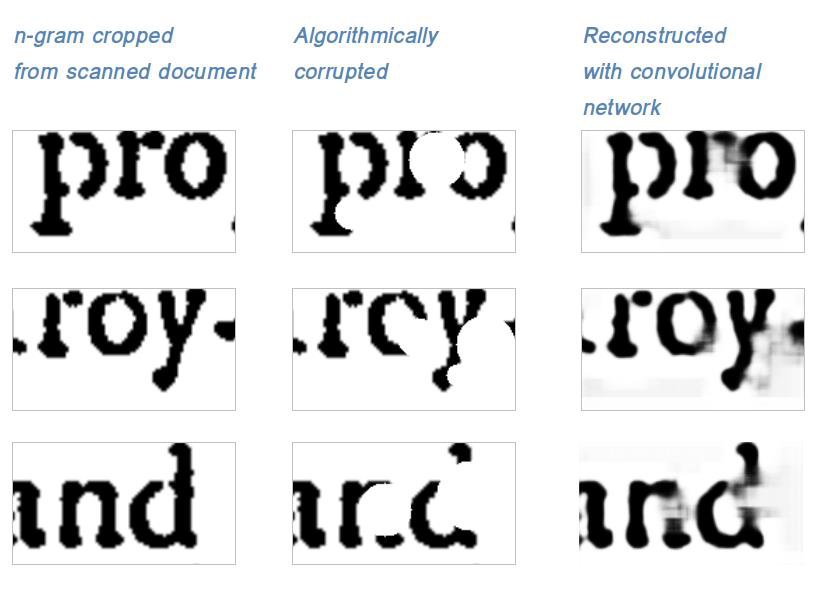

Attempt at using convolutional networks to reconstruct OCRed text.

Surprisingly I can't think of many applications of intelligent Computer Vision tasks to showcase here, even though we do host thousands of high-resolution images of manuscripts and other archival objects on our servers. One recent experiment consisted in the reconstructive pre-processing of character shapes from early 19th century printed official documents to mitigate its detrimental effect on the OCR. I’ve trained convolutional autoencoders on synthetically corrupted n-grams randomly cropped from undamaged regions of the same book. This is a form of self-supervised learning where training data is automatically derived from unlabeled samples. This is a very unconclusive work in progress that I initiated with my 10% time allowance.

One interesting observation about this approach so far is that the computational model is very sensitive to how faithfully the artificial corruption matches the natural degradation of the ink. As explained earlier, ML tends to shift the design of the problem definition to a different space; from reconstruction to (methodical) destruction in this occurrence.

What can we take away from those use cases?

AI is a very versatile and potent addition to humanities methodologies. Sometimes it can be creatively added on top of an existing digital environment to bring up alternative views over the research material (albeit without any understanding of its historical context). At other times its own creativity relieves researchers and RSEs from fully crafting novel or complex computational procedures to meet well defined objectives.

One recurrent challenge we have observed however, as illustrated twice above, is the situation where AI is foundational to a project. For instance, when primary research activities are heavily dependent on how well AI can automate very repetitive yet intelligent (or informed) data processing tasks. The experimental work needed to select, test and optimise a particular ML approach may consume a significant chunk of the budget. Worse still, there is sometimes no initial guarantee that it will lead to a sufficiently reliable and efficient system (as exemplified by this collaboration between New York’s Museum of Modern Arts and Google). Understandably non-AI researchers can be dissuaded by that level of investment and risk.

As a Digital Lab however, we must embrace and strategise some level of risk associated with the adoption of new technological methods even if AI can be especially challenging in that respect. One option described above is for the researchers and KDL to secure seed funding dedicated to that type of experimentation. Provided the problem is well specified and test data available, we can assess a few techniques, confirm feasibility and refine the development estimates of the proposed project and targeted grant application if applicable. We also deliver a working prototype and / or a detailed report to help partners navigate complexities, assess options in a more informed manner and ultimately strengthen their project foundations or funding application as appropriate.

In the future we hope to be able to involve colleagues with relevant expertise in specific areas of ML (e.g. Neural machine translation, handwriting recognition in medieval manuscripts) who would be interested in contributing to our feasibility studies. King’s Institute of Artificial Intelligence is looking at mechanisms to facilitate those collaborations not only across departments (e.g. see the expanding AI expertise in the Department of Digital Humanities, DDH) but also faculties while the RSE community is evolving in identifying fellowships that would be applicable to our team members. These sorts of collaborations would be very educational to us as we are not researchers in AI methods but research software engineers doing our best to catch up with AI.

There is appetite within our team for projects where AI is not just a supporting tool but the subject of critical exploration of possibly understudied potential, limitations and effects when it interacts with Digital Humanities methods. Deep Learning has undoubtedly brought very impressive breakthroughs to Computer Vision and Natural Language Processing. But its models are typically very dense, opaque, heavy and difficult to control. This can lead to uncritical (counter-)hype, intellectual debt, unscientific misuse, hidden biases, misrepresentations of knowledge, unstable predictions, poor modeling practices, ... KDL could facilitate close experimental analysis of the nature of ML when applied to heritage or humanities material. Such an angle, which treats emerging technologies not as mere subordinates to Humanities endeavours but instead empirically, and introspectively delves into the rich and intricate interface between the two fields would be a welcome change in project focus from time to time. By making the reliability of the technology a central research question, uncertain capabilities identified from the outset are no longer a source of risk but an opportunity to objectively inform project partners and the DH community at large about caveats and best practices.