From Cagliari to KDL: Memories of a research stay

With these few lines, I would like to describe what has been my experience at the Department of Digital Humanities at King's College of London and the King’s Digital Lab (KDL). Several weeks have now passed since my return to Italy. The leaden English sky has given way to the warm Mediterranean sun; the white foam of the Sardinian sea has replaced the slow flow of the Thames. Six months may seem like an eternity, but not when you find yourself living it in a multicultural and vibrant metropolis like London. A place with such different rhythms and opportunities than where I come from.

What brought me to the Virginia Woolf Building was the doctoral programme I am pursuing at the University of Cagliari under the scientific responsibility of professor Giampaolo Salice, and in particular the training course linked to the PON R&I scholarship I hold. This programme, entitled Forming a digital humanist: methods, tools and best practices, aims to train a researcher capable of designing and developing projects that integrate humanistic research methodologies with computational systems. So, spending a research period as visiting PhD Student at KDL, was the right choice to broaden the theoretical and practical training given to me by the Centre for Digital Humanities at the University of Cagliari, as well as by Linkalab s.r.l., the partner company of my PhD programme.

The choice may seem natural, logical, almost banal, if we do not consider the real scope behind the research I am conducting: to reconstruct the dense and complex network of economic, social and institutional relations that developed in the Tyrrhenian area between 1580 and 1640 around the fishing and marketing of Sardinian coral.

The complexity of this topic of study prompted me to adopt a research strategy that integrated the traditional methodologies of historiographical research with those learnt during the training mentioned earlier. However, this was not the only reason. In fact, my project was included in the Digital Atlas for the Maritime History of Sardinia, a research programme that aims to counter the established historiographical approach that considers the sea as extraneous to the history of Sardinia, but also pushes its participants to test methods for organising and coordinating research that originated as independent research through the use of digital resources and tools.

Indeed, as those who work in the field of digital history know, the use of computers, tools, and computational methods in historical research can improve its quality, depth, and extension, not simply to lighten and speed up the work of the researcher. However, to unlock this potential, a preliminary reflection is always needed to guide the structure of the project, the actions and the tools needed to realise it.

Thanks to the advice and suggestions of Dr Arianna Ciula (Director & Senior Research Software Analyst at the lab), this was precisely the first aspect I refined in the six months that KDL hosted me. Under her supervision, I observed the operational and management strategies used by the development team to design, realise and implement systems, infrastructures and tools behind several nascent works placed at the intersection between digital and Arts & Humanities.

This allowed me to optimise the organisation of the workflow I'm experimenting with in my research. This flow involves the use of Handwriting Text Recognition to obtain an automatic transcription of the archival documents I have selected and, subsequently, the extraction of entities (such as names of people and places) from these textual corpora through the execution of NER tasks relying on the WikiNEuRal dataset. These entities can then be used to create datasets containing, for example, all the names of all the people involved in coral fishing and trade at a given historical period in a given geographical area. Or, they could be used to map the places where those activities were carried out by using GIS software.

This mapping operation was, among other things, something I had planned to develop during my visiting period. However, after a long and careful evaluation with my KCL supervisor, Dr Andrea Ballatore, we decided not to develop it further, as my knowledge in this field was still too low, and to focus instead on historical source analysis supported by digital methods.

Indeed, beyond the opportunities offered in terms of preservation, accessibility, non-invasive study and dissemination of historical sources, digital humanities can also unlock new frontiers for historiographic knowledge. In other words, digital humanities allow for detailed forms of analysis, favouring analytical disassembly of documentary sources and a different visualisation of the information they contain.

Along these lines, thanks to the help of Geoffroy Noël (Senior Research Software Engineer at the lab), I was able to start answering one of the many problems that my research places in front of me.

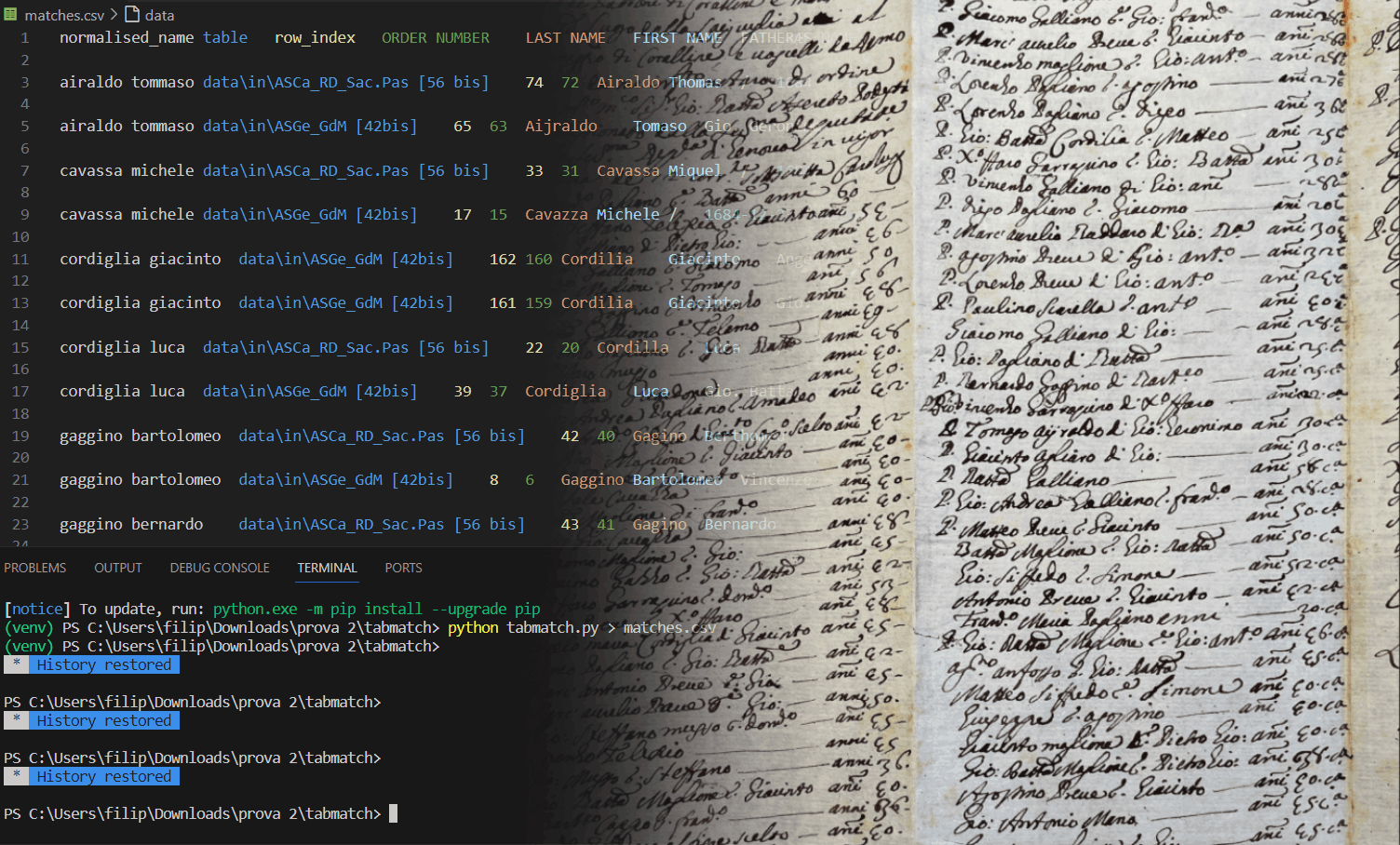

In the national archives of Genoa and Cagliari, I had located two separate documents containing the names of more than a hundred coral fishermen. Both of these documents were written in 1684 but in different languages (Italian and Spanish) and in different places (Liguria and Sardinia). So, how could I check if a fisherman was present in either of these lists of names coming from different archival contexts? After pondering the problem for a while, I concluded that a good strategy could be to develop a tool capable of automatically comparing the two lists and identifying matches between them.

Thus, I first transcribed the contents of the documents into two separate spreadsheets, organised according to the same structure based on the information I was interested in (names, surnames, ages, normalised versions of names and surnames, etc.). At the same time, Geoffroy worked at writing a small programme in Python language capable of comparing the contents of the two spreadsheets and returning the identified matches in an ordered form in a third sheet.

It may seem like a simple achievement, but thanks to this tool, I am gaining a better understanding of how these small historical figures moved and operated in their seasonal fishing activity, bringing together several documentary sources that have been interpreted separately until now.

I also believe that the historical data produced through this kind of processing could easily be shared and brought into a system with those derived from similar research, such as the ECOMEDES project led by Dr Alexandra Sapoznik, a researcher I had the opportunity to interact with during my time at King's. This could build a basis for further and more extensive analyses of the history of the Mediterranean and its economic and cultural connections over the centuries adopting a very long-term perspective.

I was very happy to be a member of King's Digital Lab team for a short period of time and have this extraordinary experience. I enriched my theoretical and methodological knowledge related to Digital History and have been able to compare the paths followed by the Italian and British academic worlds in this fast-developing disciplinary field.