Room is Sad

Room is Sad appears at the London Design Biennale until June 25th

Room is Sad is an immersive experience that uses AI and the Internet of Things (IoT) to tell the story of a smart room that isn’t feeling quite itself. It's a humorous, accessible way to engage both an academic and general audience on questions of identity, privacy, and intelligence.

Room is Sad was made in association with Charisma AI and King's Culture. The exhibition was designed by Alphabetical Design.

Writing the Room

When I was Co-I on the AI & Storytelling project, my role was to facilitate the adaptation of an immersive theatre show, King & Country by Parabolic Theatre, into a Unity game, using Charisma’s story engine to replace the performers, drawing on my experience as a Research Software Engineer (RSE) and a novelist. I ended up doing a lot more writing for the project than I expected, on King & Country and some early experiments for Charisma’s recently released Kraken. This form of writing was new to me, and I found myself becoming more interested in the strange results I was creating – the key phrases I was making for the AI to us in Natural Language Processing weren’t quite right – as what was supposed to be ‘correct.’ It was an uncanny valley effect caused by the synthetic voice and my written responses that matched up with user inputs in surprisingly jarring ways.

I’m also interested in ‘smart’ devices, because what we mean by that are devices which will do work for us. So we sacrifice autonomy for convenience, and Room is a humorous way of asking where the line is where we give up enough autonomy that the ‘smart’ thing has goals and desires of its own.

But that isn’t enough for a good story. I wanted room to be more than a technological curio, and for that I needed a story. AI is at the point where we’re amazed that a dog can play the piano, we’re not so concerned about it’s wonky tempo. Story requires character, conflict, and agency. By allowing more and more autonomy to ‘smart’ devices for our own convenience, we give them agency. The questions I then had to ask, as I do whenever I crate a character, are: what does the Room want? What are its problems, its desires, the things it dreams about?

I found I couldn’t answer these questions in a satisfying way with just Room on its own, so as it evolved I started looking at everything in the space as a potential character, to give more scope for interaction. That is how the lamp, plant, and desk end up being active parts of the story, in something like a workplace sitcom. The plastic plant is its best friend, but Room is worried about what it thinks of it. The desk has done something to make Room angry, but it is reluctant to discuss it. The lamp, on the other hand, remains blissfully ignorant of the seething workplace conflicting going on around it, as it believes only in light and darkness.

The participant wanders into this tangle of inanimate object angst. They can be an impartial observer, a peacemaker, or deliberately cause trouble. It’s up to them.

The Technology

- Charisma AI. A branching storytelling engine that uses Natural Language Processing (NLP) to understand users and serve responses. This is how the Room talks and understands players.

- Internet of Things (IoT). Smart bulbs run by a smart home platform called Home Assistant. UWB radios give me a precise location for the player and some props (the plant) using sensors.

- Unreal Engine 5. Serves as the director of the experience, tying everything together. It does the UI and passes messages to Charisma and Home Assistant. It uses Charisma’s SDK and a plugin for MQTT communication with Home Assistant from Nineva Studios.

AI Guest Stars

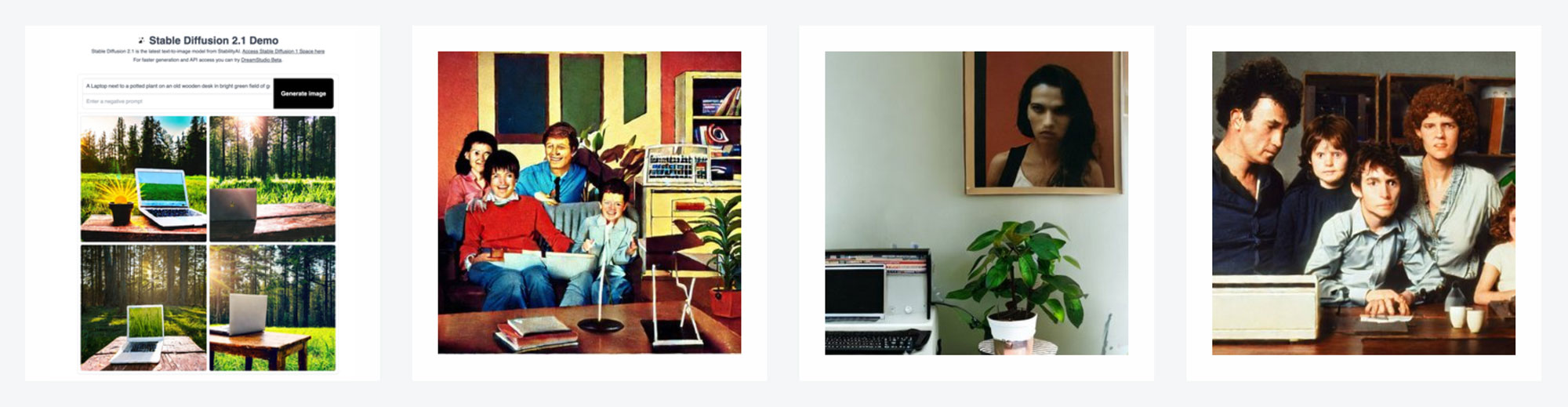

I decided to use generative AI to provide some elements of Room’s mind. First, I used Stable Diffusion to visually represent its mood and subconscious, using basic prompts:

- "Laptop and potted plant holding hands and skipping through a green field of grass with a bright yellow sun shining down"

- "a happy family with two adults and two kids relaxing in an eighties living room with a plant, a desk lamp, and an old computer on a wooden desk in the background in a magazine advertisement style"

- "A sad family in an 80s living room"

- "a photograph of a frowning person in a living room with a plant, old computer, and lamp"

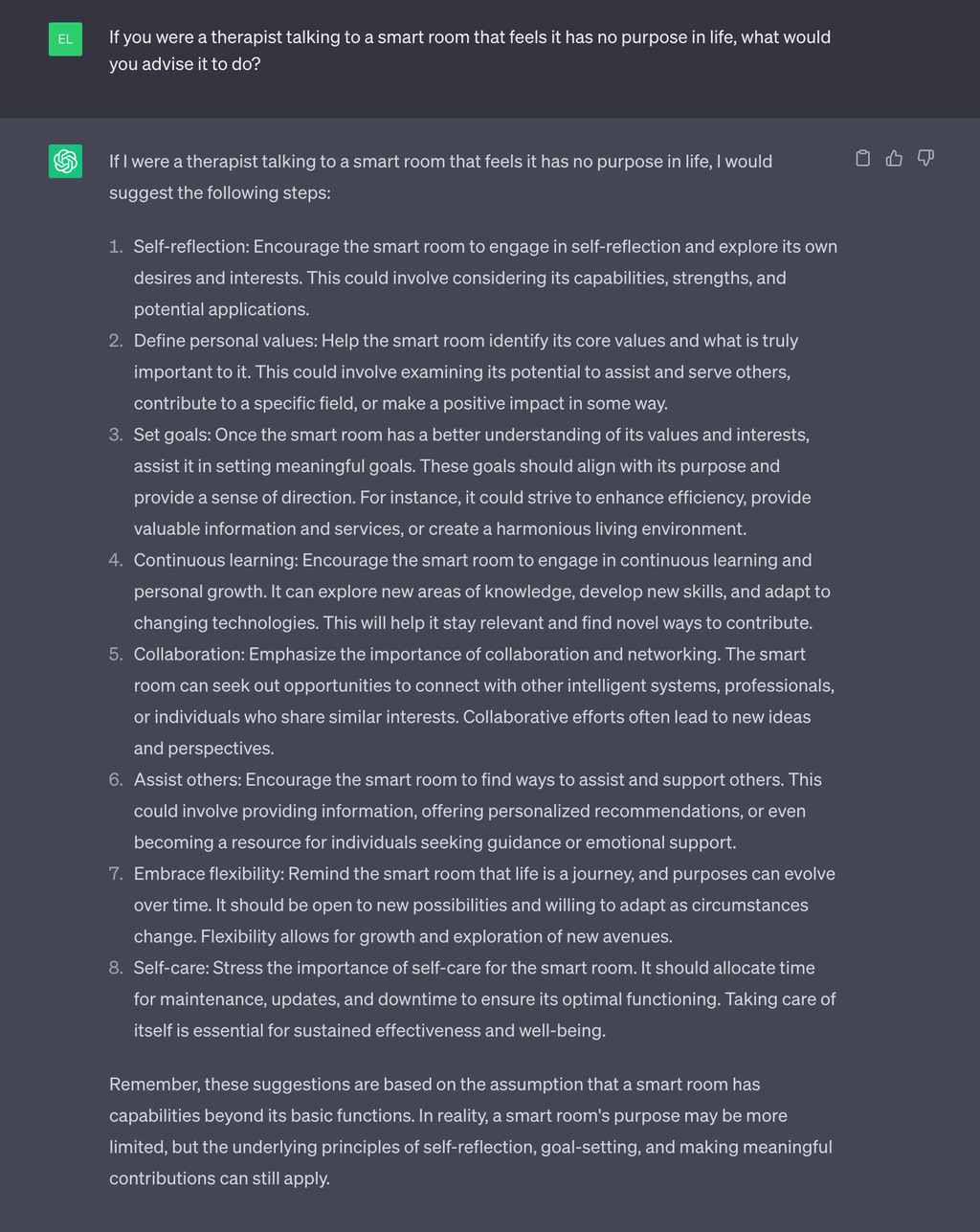

I also used OpenAI's Chat GPT-4, though not to write any of Room itself, for reasons I hope to go into in a later post. The short version is that I wanted GPT-4 to be a character on its own, so I made it into Room’s therapist. Here is the therapy session, that I then cut down for use in the installation:

Room's therapy session with GPT-4

This was an interesting contrast for me to the rolling panic about generative AI, especially among creatives who wonder if they are being replaced anytime soon. It certainly enabled me to create some weird images I wouldn’t have been able to do on my own, but I used these tools precisely for that unsettling affect – the odd turns of phrase, the slightly melted faces in the happy families – rather than any desire to replace artists or writers. The artificiality was the point.

Background to the project

Room is Sad grew out of two previous projects I’ve done for KDL in 2019: AI & Storytelling– an Innovate-funded collaboration between KDL, CMCI, & Charisma AI, and The Digital Ghost Hunt series – initially funded by UKRI, with Sussex and KIT Theatre. AI & Storytelling was a collaborative project with Charisma, leveraging the cultural production experience of Prof. James Smithies (Digital Humanities) and Prof. Sarah Atkinson’s work on bias in AI. The Charisma storytelling engine is what powers Room as a character. The idea of a smart room with emotional problems first came from that work. I wrote a brief writeup about it for possible inclusion in a forthcoming King’s event.

Then the pandemic happened, and I forgot about it completely. Fast forward to about six months ago, and my original proposal was found in a drawer. In the meantime I’d also done several more shows in the Digital Ghost Hunt series with KIT Theatre, and I was interested in combining that spatial work I’d done in that show to explore the physical embodiment of AI as in a physical presence. My work with Ultrawideband Radio (UWB) allowed me to give the AI a physical dimension. I was encouraged to apply for inclusion in Eureka at the London Design Biennale and, to my surprise, they found the idea reasonable.

I was able to develop the idea under the lab’s ‘Ten Percent’ program, which allows me to devote some of my time to exploratory research. This program has provided incubation support for most of the work mentioned here, and led directly to funded projects like The Digital Ghost Hunt. It's part of the Digital Creativity theme, a core research interest for KDL that focuses on research and co-creation with the creative industries.

Reception (so far)

At the time of writing the project has been used by about a thousand users. When the Biennale finishes on the 25th, I’m going to go through the responses in detail, but the limited interactions I’ve watched have already turned up some interesesting and unexpected responses.

Right now there is a seemingly endless series of lurid articles about how AI is going to take our jobs and/or our lives. Room’s confusion and everyday concerns create a vulnerability you don’t see much right now in AI. For that reason people warm to Room more than I expected. AI are meant to be omniscient, maybe terrifying, machines. Room is in no condition to be part of the robot revolution.

The future

Room is an installation but it’s also a proof of concept for merging AI with spatial work and immersive theatre. With a bit more… room I can expand the range of interactions that can be informed by where players and objects are in space.

In the meantime, we’re exploring with King’s Culture remounting Room in the Bush Arcade later in the year.