Critical Modelling of Extensive Literary Data

Authors: Katherine Bode, Arianna Ciula, Galen Cuthbertson, Geoff Hinchcliffe, Ginestra Ferraro, Miguel Vieira, and Millicent Weber

This blogpost discusses and reflects on the process and findings of the collaboration between colleagues at the Australian National University (ANU) and at King’s Digital Lab (KDL), supported by the King’s College London Australia Partnership Seed Fund and Australian National University Global Research Partnership scheme, for the period 2020-22. It provides some background and outlines three approaches to investigating the Reading at the Interface project dataset.

Background

The Reading at the Interface (RTI) dataset was generated between 2018 and 2022 by querying a range of platforms (social media, newspaper, and academic) using AustLit records of works of Australian literature, published between 1788 and 2018, in a range of “forms” (including children’s fiction, essays, novels, novellas, poetry and short stories). The forthcoming platform ANU aims to launch in due course will publish the data in two ways:

- via an API, that will allow others to query it in something close to the form of the dataset (some copyright issues pending);

- via a bespoke user interface or interfaces for engaging with the textual data.

This approach is driven by a core interest in exploring the question of what textual data is or should or might be for humanities disciplines. At present, digital humanities projects, including (or perhaps, especially) in computational literary studies, explore textual data in ways that follow what we might call “structural” or even “structuralist” principles. According to this understanding, culture and language are systems in which meaning is determined by their structures. The relationship between culture and language is considered arbitrary but can also be studied in order to understand how both work.

All of the methods used in this collaboration between ANU and KDL teams have structuralist roots, in that NLP parts of speech, word and sentence embeddings, and large language models are premised on the notion that finding relations among parts of a whole (a sentence, a corpus, other ‘linguistic’ units) is a way of uncovering the operations by which meaning exists.

The Problem

The problem we see with this approach is that very few areas of inquiry in the humanities hold to structuralist explanations or to predetermined relations across defined units of analysis. Rather than systems having structures that determine meanings that can be interpreted by subjects, the general move across the humanities is “poststructuralist” - i.e. it understands subjects (and objects and situations) as created by systems that they also create, or less strongly, shaped by systems that they shape. Because language, for instance, is understood as a condition of being a subject, there is no place outside of language from which to see the structures it supposedly contains. Another problem is that this structuralist approach is at odds with the way that textual transmission is generally understood in humanities disciplines such as textual and media studies: as bound up in or inseparable from both the material forms with which it is expressed, and the social forms in which it is received.

Techniques of reading and writing (or reading-writing, to emphasise the extent to which each requires the other) and technologies such as the book have been the practices with which humanities disciplines have made meaning, and these cannot be separated from design. Though they have structure, they do not presume structure determines meaning, which instead arises from experiences that shape or even create its participants.

Our experiment

The ANU/KDL experiment in playing with and publishing textual data tries to understand whether it is possible to use structuralist methods without fully subscribing to their logic, and to do so in ways that are attentive to the importance of materiality and sociality, to their capacity to mean anything, and ultimately to producing their simultaneous determinacy and indeterminacy.

Inspirations and aspirations

Here are some sources of inspiration:

In 1985, D. F. McKenzie wrote:

The procedural constraints that traditional textualities lay upon the larger semeiotic field that they model and simulate are far more pragmatic, in a full Peircean sense, than the electronic models that we are currently deploying. [...] Digital tools have yet to develop models for displaying and replicating the self-reflexive operations of bibliographical tools, which alone are operations for thinking and communicating—which is to say, for transforming storage into memory, and data into knowledge. [...] Traditional textuality provides us with autopoietic models that have been engineered as effective analytic tools. The codex is the greatest and most famous of these. Our problem is imagining ways to recode them for digital space. To do that we have to conceive formal models for autopoietic processes that can be written as computer software programs.

(McKenzie, 1985)

However, as McGann (2014) states, the models we use in those systems have limits:

It should also be remembered that it was not the sophistication of computing in its early stages which biased its use towards science, but its limited memory and therefore its inability to handle the complexity and range of verbal language as distinct from combinations of the numbers 0 to 9. Only as its memory systems have grown has the computer changed its nature from blackboard to book. It has at long last become literate and qualified to join other textual systems.

(McGann, 2014)

Generative AI advances might very well challenge these limits and are in fact making researchers question the essence of reading-writing and how that practice is acquired and thought of in humanities disciplines. Regardless, our question is in what ways are our approaches of engaging with digital textual technologies still bound by structuralist assumptions, and in what ways can they build on and develop textual technologies appropriate for new situations and practices? Or in Fazi’s words (2018) is a “digital aesthetics” possible?

Of the codex technology in the context of the development of the novel in the eighteenth-century, Christina Lupton writes that: “the book [is] a machine that embodies contingency” (1187) because it “doubles as a sign of an already determined future, and as a sign of openness to the incalculable,” (1189) with “its pages bound and yet open to permutation” (1173). Contingency, as Lupton defines it, is not a synonym for chance but a proposition from which both “necessity and impossibility” are excluded. Seltzer discusses contingency in these terms as a way of “acting confidently and building descriptions of the world out of the unknown and out of knowing about nonknowing, since there’s no alternative anyway”. Fazi (2018) likewise argues that “contingent formalism” and hence “generative capacity” are at the heart of digital computation:

Computation’s preprogrammed procedures should be understood not as an all-encompassing and preformed total determinism, but as processes of determination that are always exposed to, and in fact ingressed by, indeterminacy.

(Fazi, 2018)

Design-first approaches offer another source of inspiration. The visual examples quoted below are grounded on (often textual) data trustworthiness, yet work with readers’ perception and foreground the creative process not availed of technical functionalism.

Images clockwise from top left: Stefanie Posavec; Hanna Piotrowska; Stefanie Posavec again; Nicholas Felton

Are we able to design systems for contemporary textual data that operate like the codex, fixing things in place without suggesting that they are structurally predetermined to be that way, and creating the relations in which or through which engagement can occur without predetermining what will be done and how? Can these be generative in virtue of their structures rather than despite it?

Experimental modes

The three structuralist modes of text-arrangement we have experimented with are:

- NLP parts of speech (led by Geoff)

- Exploring textual data with notebooks (led by Miguel)

- Large language models (or potentially a simple method for designating entropy) (led by Galen)

They are outlined below by reflecting on the interests of each lead experimenter and produced artefacts (notebooks, code and design assets).

NLP Parts of speech (by Geoff)

Interests:

- Exploring alternatives for aggregating RTI reviews content.

- Developing approaches that could be deployed for public interaction.

- Developing novel modes of representation and interaction.

Working with large textual datasets, like the corpus in this project, the questions we ask are dictated by the structures and qualities of the data. A key focus of this experiment was to consider how we might work outside the familiar structures that dominate our understanding of the data; beyond the connections of reviews to works and works to reviews, how else can we think about the data? This experiment aims not to consider what is being reviewed, nor who is reviewing, but how works are being discussed.

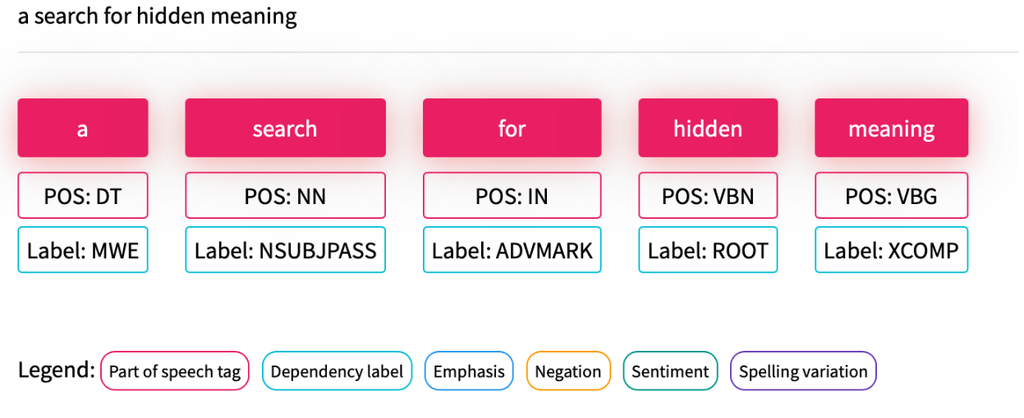

To explore this idea, I decided to use Parts Of Speech (POS) tagging. A POS process involves tagging each word in a sentence using a lexical tag set; noun, verb, adjective, or other grammatical category. There are around 36 different tags in a typical NLP POS library such as the Penn Treebank Project. Tagging is dependent on the relational context of each word, rather than using a static mapping between word and tag. My hunch was that POS encoding could show us something about how, in a grammatical sense, people were discussing Australian literature and use POS tagging to draw together review texts that would otherwise have no relation.

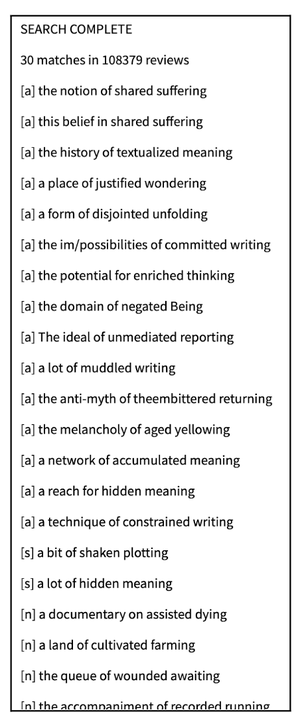

To test this hunch, I used the Fin NLP POS Tagger to encode the review texts as POS and saved them as flat text files. I then created a JavaScript web app which encodes a user’s text input into a POS string and finds matching patterns in the POS encoded review files, displaying matching texts as a list.

A user’s text input is encoded as POS.

The list of matches, denoted by source (review publication type): [a]cademic, [s]ocial (media), [n]ewspaper.

The results the app produces can be satisfyingly recognisable and also curiously oblique. The relevance of some results is clear and for others much less so, however, they consistently appear plausible and avoid the sense of being entirely random and meaningless. Ultimately, it feels like there is something there even if you’re unsure what it is, or why exactly the match has been made.

As I’ve written about elsewhere, the choice to work in the web browser is a strategic one. It allows me to experiment freely without dependence on exclusive infrastructure or proprietary systems, and makes the task of deploying for a public audience a relatively easy one. This experiment is one of many I have conducted on the RTI corpus, and sees me working in an iterative reflective cycle of experimentation; apply a technique, evaluate the results, reflect on if / how the technique could be used, adjust and repeat or move on to another approach.

In terms of the key goals; the POS approach does offer potential to explore how the literary works are being discussed by reviewers and provides a means for drawing together review texts that is not dependent on the overt structures of the metadata but instead utilises the inherent qualities of the texts themselves. This initial prototype aimed only to test the viability of the POS approach, and having demonstrated its feasibility, future work will explore the opportunity for interesting modes of interaction and representation.

Exploring Textual Data with Notebooks (by Miguel)

Interests:

- Data exploration and machine learning as a means to discovery and finding new ways to visualise textual data.

- Use of notebooks as a way to share not only the results of investigations around textual data but also the thought process behind them.

Explorations, data dimensions and assets:

Notebooks, interactive documents that combine code, data and documentation, are a powerful tool for data exploration and machine learning, enabling researchers to discover new ways to visualise textual data and share their thought processes with others. They provide a flexible and collaborative environment for exploring data, experimenting with different algorithms, and creating visualisations to communicate findings.

KDL experimented with data exploration and machine learning techniques to analyse a large collection of literary works and their reviews. We used notebooks to share not only the results of the investigations but also the thought process behind them, demonstrating the use of notebooks to collaborate and share knowledge.

The first notebook we created was designed for data exploration, to get a better understanding of the textual data. The data consists of around 615,000 literary works with corresponding metadata, and also 65,000 reviews for which the text of the review was available. We created new dimensions, such as the sentiment and n-grams of the text of the reviews, which were used to experiment with different types of visualisations.

The second notebook was focused on temporal exploration and aimed to understand how the data evolved over time. Unlike the first notebook, this one didn’t focus on the text of the reviews, but rather on dimensions around the text, such as work metadata and the sentiment of the reviews. By exploring cyclical patterns in the data, we could analyse how the reviews evolved over time.

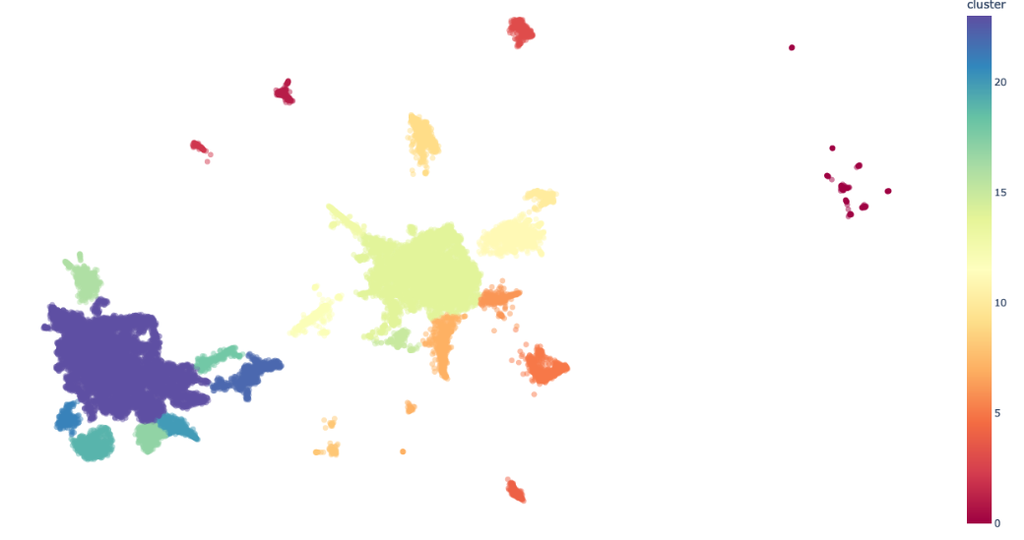

The final notebook used machine learning to create sentence embeddings. Sentence embeddings are mathematical representations of sentences that capture their features and are used for computational processing of sentence data. These can then be used for several applications, in this project it was used for semantic search and clustering. This allows us to search and find reviews based on context and meaning rather than just keywords, making it easier to identify patterns in the data. We also explored different visualisations to represent the embeddings.

Sentence embeddings of the RTI reviews (academic, social and newspapers) coloured by cluster

Elements of the final exploration will be integrated into the Reading at the Interface platform.

Entropy in Large Language Models

Interests:

- Exploring the relationship between concepts of 'surprise', 'entropy', and commonsense user understandings of 'interesting content'.

- Resisting 'generative' paradigms of Large Language Model use.

- Developing unusual or 'alien' metrics for intuitive exploration of the corpus.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have grown rapidly in scale and popularity; however, the majority of scholarly and popular attention has been on the generative capacities of these models, and the capabilities which appear in response to specific prompts. In my exploration of the Reading at the Interface dataset, I sought to shift focus towards the inverse: rather than examining the extent to which a given LLM (such as GPT-3) could generate compelling text, I sought to measure the extent to which each review in the dataset was 'well-modelled' by the LLM. For each review, the questions are counterfactual:

- How likely is it that an LLM would have generated this review?

- On a scale from 'human' to 'machine', how 'human' is this review?

- Or, to use more historical terminology: from the perspective of the model, how much 'information' is in this review?

In ‘Prediction and Entropy of Printed English’, Claude Shannon provided a useful definition of character-wise information in language:

The entropy is a statistical parameter which measures, in a certain sense, how much information is produced on the average for each letter of a text in the language. If the language is translated into binary digits (0 or 1) in the most efficient way, the entropy is the average number of binary digits required per letter of the original language.

Shannon was commenting on the entropy of a language using a per-character measure — something that can only be approximated empirically — but his intuitive account of the 'entropy' of a text is closely entangled with modern, token-based approaches. While the performance of pre-trained LLMs today is often measured in terms of downstream tasks — as exemplified by the GLUE benchmark — training of the models themselves is governed by a more basic measure: perplexity, the exponentiated average negative log-likelihood of a sequence. This is, in essence, a measure of a model's ability to predict each token in a text given the previous tokens in that sequence; the cross-entropy between the data and the model's predictions. A text with lower 'perplexity' is one which is more predictable by the model.

My explorations of this began with use of OpenAI's GPT-3 API. Unfortunately, three entangled challenges emerged. First, the lack of access to the underlying model, combined with the limited nature of the API output, meant that it was impossible to access the log-probability for each token in a sequence. Second, I discovered that the only way to access the log-probability of a given token was to repeatedly query the API for each token in a text string. The scale of our corpus meant that this would be prohibitively expensive. And, finally, relying on a closed model meant sacrificing the replicability of our experiment (and possible interface).

Here, the unintended release of Meta AI's LLaMA model offered a solution. Thanks to the efforts of the open source community in developing optimisations such as 'llama.cpp' and high-level wrappers such as 'dalai', it is now possible for us to generate an accurate perplexity measure on our own hardware, with full access to the log-probability of each token in a given review. While still computationally costly, we now have the ability to generate an accurate measure of perplexity which is complete and replicable. Critically, this measure can also be integrated into an interface for measuring user input, enabling us to compare collected reviews to user-generated contributions without relying on an external corporation which may change or remove model access at any time.

What next?

We collaborated remotely, sometimes severely impacted by the material disruptions of climate change and COVID-19 pandemic.

While our experiment did not have a definite outcome in mind in terms of delivery of design products and interfaces, we attempted to remain true to a Research Software Engineering perspective, driven by the objective of making something that works (for which structure - meaning reduction, parametrization, metrics etc. is a sine qua non) and sharing our results in diverse ways (Notebooks, blogpost, workshop). However, at the same time we embedded perspectives and openness of interpretation with a certain playfulness and indeterminacy of process both in the creation of the experimental modes and hopefully in its fruition once online. Some modes of our data explorations will feed into the forthcoming digital platform AWRI: A Reading-Writing Interface.